What's there to bring up... Hisaishi... Ni no Kuni II... those two names together alone are already enough to make my mouth water ;)

Well, if all those composers from Europe could learn English when they joined Hollywood in the 30s and 40s, then I expect that learning Japanese won't be an issue for anyone who wants to compose in Japan nowadays. Do a couple commercials and Visual Novels, and then after a while the big TV and video game gigs would start rolling in. I've seen a lot of up-and-coming composers salivate at the idea of having actual live instruments to work with and no temp tracks, both of which are the bare minimum standard for anime soundtracks. Those who want to just play with some samples and synths like Tyler Bates can just stay in Hollywood. I think the only thing really physically holding people back is the fact that living in Japan (especially Tokyo where all music is recorded and all studios are located) is insanely pricey and working with large orchestras is impossible unless they plan to frequent Warsaw. But the most popular reason is that working on dumb anime has no prestige in their eyes, even though it would arguably give them more freedom than any job they could get being contracted to Media Ventures.

There's hundreds of talented and trained composers like Evan Call that graduate from top-of-the-line music colleges each year, and I doubt that many would be happy to make a career out of copying Zimmer. Had Evan decided to join Hollywood he would have most likely been relegated to being either an orchestrator or a ghostwriter.

I get what you mean but that is an essential question for any musician: Do you want to pursue the art or are you content with taking the money. Current Hollywood composers demonstarte that if you just want to live the luxury life as a composer... fuck education, fuck classical training, fuck this dumb "artform", fuck honoring past generations, fuck being remembered in 300 years and all that and just copy the same thing everybody else does and put some dubstep and drumloops over it... bam! Two million dollar paycheck!!! for a movie everybody will forget in six months.

Or you pursue the "art", research where classical education and past generations of musicians are still being held in the highest honor with the greatest amount of admiration, dedicatition and love and just go there, even if the pay is not great. Evan Call specifically mentioned in an interview that the pay is not great but he couldn't be happier in his life, actually meeting the idol of his dreams (Iwasaki) in person and expressing himself freely with the usual anime guideline "just do what you feel is best for the project". And I hold the belief that limitations channel great art. Most Japanese composers are just incredibly skilled, working decades with smallscale ensembles and orchestras that if you actually let them loose on a giant symphony orchestra you get in my humble opinion the most amazing orchestral scores of the 21st century. Japan right now is the same work environment as Golden Age Hollywood, the level at which these people in Tokyo operate is just another league apart from the rest of the world these days.

Which brings me (thanks to Zipper's baton pass) to a major setpiece I was going to release before the forum went down. It's quite long, so take your time. It's essentially my Volume 3 of my introduction to the wonder of Japan I posted above. I'll also make a separate thread for it, I've done much research on the following topic, and I'm quite satisfied how this turned out:

Apart from my Legacy project, there was one more massive project I did pursue in earnest. I’ve put the finishing touches on it this morning and just as this forum opens itself anew, I believe the time has come to post it:

The further I did some actual research why Japan works the way it does to keep people like me happy and how it took over the torch of classical and jazz music, I simply have to correct some of my points I made some years ago. I once stated in a comparison to Hollywood that Japan/Tokyo is no magical music wonderland and it has dozens of mediocre/bad music too… but after I digged quite deep into the subject for my own research and interest and I hope your amazement, I simply have to correct that statement. JAPAN IS A WORLD WONDER, and it goes far beyond just music, they avoided the hellhole of postmodernism, gave it the middle finger and are celebrating and living a universal standard of arts as well as the accumulation of the cultural heritages of the world on their little island.

From Vienna classical to Golden Times Americana to 60s Britain, Tokyo is a melting pot of cultures in its purest form, in lifestyle, media and music. It can be heard, seen and tasted everywhere in their daily lives and our best cultural exports have evolved over there and have now merged with their own culture as well. This also falls in line with my prior research about the Japanese special awareness for cultural preservation. The effort to make anime/game music part of human cultural and human civilization for example is no laughing matter to them, yes, the people pushing it truly believe in their cause of making anime/game music be a natural evolution of classical music.

And who can respite the main philosophy of the biggest Japanese Music Arts association that is working behind the scenes, hand in hand with similar organizations that make it possible that about a billion orchestra concerts are happening right now…

"Where there are people, there need be dreams. The inspiration of experiencing true art gives people energy for living. We will continue to present the world's most moving performances.

We invite to Japan leading international classical musicians and overseas groups such as opera and ballet companies, orchestras, and chamber ensembles, we will organize performances in the Tokyo area and secure venues and carry out ticket sales.

In recent Years Japanese artists have been achieving remarkable success as well throughout the world, and we also continue to strengthen our efforts in support of these artists’ international activities.

We plan to produce many concerts to support the activities of outstanding Japanese musicians, and also represent them in overseas engagements.

While responding to the rapidly changing global situation, we will be truly happy if we can continue to work in cooperation and share timeless, unchanging values while celebrating differences in country and culture.

We will continue to devote our efforts to bringing inspiration and riches of the heart and mind to as many people as possible through magnificent art.”

- Japan Arts

I have prepared two essays to illustrate this point: One on classical music (European culture) by pianist and violinist Josephine Yang on the Renaissance of classical music in Japan and one on Jazz (American Culture) and general machinations of Tokyo by Journalist Tom Downey. I highly recommend to read them before diving into the following collection. It’s perhaps not the one where I put my equipment to the test but I carefully selected various pieces out of millions and put some hours of care into arranging them to illustrate my point and the content of the essays the best.

Japanese media composers are by and large NOT film composers. We may put too much focus on the film music aspect (granted some of us live in that world) and not notice the bigger spectrum. They are ORCHESTRAL ARTISTS first, influenced by all kinds of music culture all around the world, clothed with the power of the world’s most astounding music education system. Sometimes they take on the mantle of classical composers, sometimes jazz composers and yes, sometimes film composers but no category overwhelms another unless a specific artist has a specific taste or a project has a very exclusive demand or locked-picture scoring. And almost any composer working over there should have no problem launching into each field of music because of this:

“Music education begins at age 6 and lasts as a mandatory class until age 15 (during elementary and junior high schools). In elementary schools, music is taught as an independent subject either by the regular class teacher or by a specialized music teacher. Students learn to play recorders and sing. In junior high schools, music is taught as a separate subject, and starting from junior high, the students learn how to play traditional Japanese instruments as well. At this point in their education, 100% of students in both public and private schools have been exposed to western classical music. Music classes become optional electives at the senior high school levels, and ensembles like bands, choirs, orchestra, etc. congregate in sessions after normal school hours. The normal Japanese education timeline is: 6 years in elementary school (sho-gakko), 3 years in junior high school (chu-gakko), and 3 years in senior high school (koto-gakko). Solfege is taught with the fixed-do system, unlike most American institutions that teach movable-do.” (read the essay!)

And even though I’m not a fan of Yokoyama’s work, he can at least write a classical piece and jazz at a competent level, same goes for Hayashi (Jazz is his strongest game I feel) and Kajiura. Among popular composers there’s really only Sawano and Sagisu that I feel are a bit clueless or far too simple on what they are doing, BUT Sagisu manages to be a great pop musician to compensate with some genuine sparks on a soundtrack (his earlier stuff in particular) and Sawano at least sounds totally unique in the Japanese soundworld and does that RC wall of sound far better than RC themselves with the exception of Zimmer in my opinion, and hey, the more flavors the better.

But without further ado, here’s the first essay:

Tokyo’s Thriving Classical Music Culture

Part 1: The centre of classical music in the 21st century?

"The country has shown an extraordinary devotion to Western music for 140 years." - Ivan Hewett

Where is the nerve centre of classical music in the early 21st century? Answering that question depends on your criteria. If it's to do with possessing a venerable tradition, you might choose Vienna. If it's the location of the best orchestras and opera houses, you might choose Berlin. If it's finding exuberantly creative ways to reinvent the tradition, London or New York seem strong contenders. But if the true measure is a passionate devotion amounting almost to idolatry, Tokyo would win the palm.

It's revealed in a thousand ways, not least in the sweetly earnest way people talk about the art form. The president of the Japan Arts Corporation wrote in his company's concert brochure that "music has the power to foster a richer greater experience for the human soul." Audiences listen in a silence that one can only describe as fervent. At one concert in Tokyo, my neighbour sat perfectly still, eyes closed, for the entire three hours of Bach's St Matthew Passion, with only a tiny rhythmic movement of his little finger to show that he was still alive.

Many factors come together in the Japanese love affair with classical music, some ancient, some new. The most obvious factor is fairly recent - Japan's decision in 1868 to end centuries of isolation and open itself to the West. One of the first imports was Western music. By 1872 Western music had supplanted traditional music in the Japanese school system, and in 1884 the philosopher Shoichi Toyama actually suggested that Christianity should be adopted because it would help the new music to take root.

Another advantage of Western music was that it seemed better suited to modern sensibilities than the old traditional songs. The writer Nagai Kafu, who studied in Paris, remarked sadly that "no matter how much I wanted to sing Western songs, they were all very difficult. Had I, born in Japan, no choice but to sing Japanese songs? Was there a Japanese song that expressed my present sentiment - a traveller who had immersed himself in love and the arts in France but was now going back to the extreme end of the Orient where only death would follow monotonous life? I felt forsaken. I belonged to a nation that had no music to express swelling emotions and agonised feelings."

But Kafu lived long enough to see that his fears were unfounded. Japan embraced Western ways as its own, a process only briefly interrupted by the Second World War. By the 1950s, Japan had its own artists' agency, and foreign artists were again visiting the country.

At first, the cost was prohibitive. Kaz Nakaya, a retired university English professor and self-confessed opera buff, says that when he first became interested in classical music an LP cost as much as an average month's salary. But the upward momentum was unstoppable. Japan was by now no longer an importer of Western music; it had its own orchestras, some of which, such as the Tokyo Philharmonic, had quite long histories. It had several distinguished manufacturers of pianos and other instruments, which were serious rivals to Western firms. It had its own performing virtuosi, and its own composers, one of whom, Toru Takemitsu, had a worldwide reputation. (The Telegraph, UK, 2006/5)

Part 2: One City, 8 Full-Time Orchestras!

Classical music is not dying out. When I hear the opposite statement being expressed, I have to stifle a sigh — not a reaction of blind optimism, but of my acknowledgment of active organizations successfully bringing great, living music to large and diverse audiences.

One of the most common criticisms of classical music is that it’s too stuffy or exclusive. Being “different” or “exclusive” in classical music is simply an illusion: isn’t exclusivity a part of any culture or practice? And truly, classical music is no less welcoming than jazz, musical theatre, indie, folk, or even popular music.

With all forms of music, there is a certain pride that comes with familiarity and being educated in the field. This holds true even with pop music. American society is so inundated with it that we’re expected to know names and songs of certain pop celebrities, and we almost couldn’t run away if we wanted. As a result, we’re often judged as having antiquated tastes if we happen to be clueless. The feeling of exclusivity in any field happens mostly because people have gotten excited enough about the subject that they have chosen to invest their time and money in it. Consequently, they’ve built up a certain pride in the attainment of knowledge or skill, and some handle it quietly and humbly while others may express themselves differently.

Actually, people are much more receptive to classical music than most think. For instance, all our greatest films would be horribly, painfully awkward without their soundtracks. Remember this video of the Star Wars Throne Room scene, minus John Williams? (And I do consider film music a type of classical music, but more about that in a future blog post.)

So again, classical music is very much alive. That being said, the music is brought to people by various organizations, so it’s always important to acknowledge specific organizations and cultures that manage it well. In my experience thus far of traveling and observing how classical music is received in various cultures, I was most impressed with Tokyo’s overall receptiveness to and integration of classical music, while keeping in mind that this genre of music is a fairly recent import to Japan.

I’ve been to Japan twice: the first time in 2014 to witness conductor Keitaro Harada’s incredible Japan debut with the New Japan Philharmonic in a winter trip that lasted all of four days, and last summer of 2015, when I spent five weeks in Tokyo. Both times, I was awed by the accessibility of classical music and at the respect the people have for music. I’ve been quite fascinated by this, and it’s a topic that repeatedly gets brought up in conversation. It’s about time I wrote a post about all the things that shocked me so much about how music (namely, classical music and cultural music) is presented in Japanese life, with further research to clarify my impressions. While classical music is a thriving entity in Tokyo culture, I believe that the main catalyst for this is the built-in importance of meaningful music in everyday life, whether it’s culturally-significant folk music or classical (some of which really has become as culturally significant as traditional melodies which originated in Japan). While most of this blog post is about classical music, I will also discuss how music in a broader sense is brought to the people.

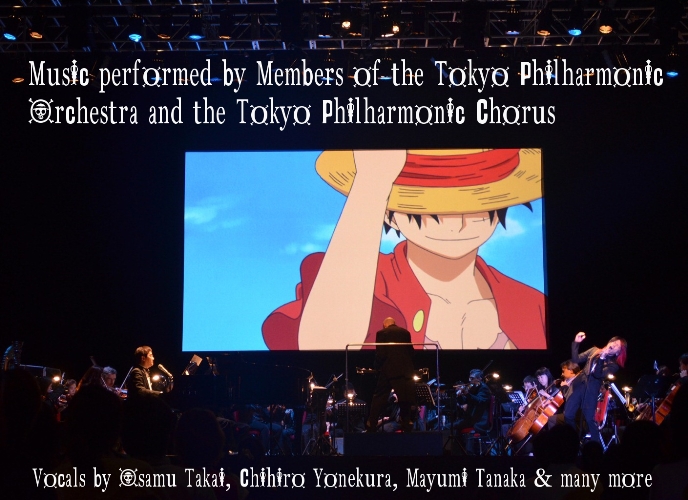

Tokyo is saturated with classical music. In just this city, there are EIGHT professional, full-time orchestras that total over 1,200 concerts a year: NHK Symphony Orchestra, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo City Philharmonic, Japan Philharmonic, New Japan Philharmonic, Tokyo Philharmonic, and Tokyo Symphony. Though the names are amusingly similar, each organization is separate and unique. In all of Japan, there are 1,600 orchestras (professional and amateur) — all in a country with a land area that’s smaller than the state of California but holds a population that’s about 40% of the United States! To put things into perspective, the United States would need about 38,000 orchestras to equal that percentage.

Additionally, these concerts are very well-attended. The halls are usually 85-95% full, and the demographic ranges widely in age with many young people in the audience. The dress code is fairly casual, ticket prices are accessible from US $30-120, and evening concerts usually begin at 7 pm. The Japanese audiences are very respectful and quiet from my experience, which isn’t surprising at all considering the widespread societal aversion to acting out. Programming is also pretty standard. In the 10 concerts I attended in five weeks, I didn’t hear anything past Bartok and Stravinsky. Bruckner is interestingly noted to sell out concerts very well. This suited me just fine since I fell in love with the composer after hearing Herbert Blomstedt conduct Bruckner 9 with the LA Phil in a performance that was nothing short of transcendent. Program books are dense and packed with separate flyers for future concerts. Also, most of the orchestra members are Japanese. On the other hand, most of the conductors were European, even while it seems to be quite a trendy thing for Japanese men to want to be conductors.

Part 3: The history of western music in Japan, and Japan’s current music education

How did Western classical music become such a huge part of Japanese culture? I was curious and did a bit of research to find out the origins of this cross-cultural exchange.

Japanese art music originates with shōmyou Buddhist chants, which gradually developed into festival music, nō, and kabuki theater music. The Tokugawa Shogunate of the Edo period (1603-1867) in Japanese history closed the country’s doors to other nations, cutting off trade of goods, ideas, religion, and art. Japan remained this way for two centuries from 1641-1854, when the United States and Japan signed the Treaty of Kanagawa, which reopened Japan to foreigners. This treaty ushered in the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), during which Japan emerged as a competitive modernized nation. International trade and influence rushed in, and Japan’s leaders attempted to modernize by emulating Western culture, practices, and thought — including music. Minzoku ongaku, or folk music, was gradually displaced by Western classical music, which they simply referred to as ongaku (“music”).

Public school music education began to show this development: Isawa Shūji, a member of a Meiji education search team, and Luther Whiting Mason, a Boston music teacher, teamed up to organize music education in Japan. In 1880, Mason traveled to Japan to create a music curriculum and to begin training teachers. The first children’s songbook, the Shōgaku shōkashū (1881), combined Western pieces that sounded pentatonic (such as “The Bluebells of Scotland,” “Auld Lang Syne,” and Stephen Foster’s songs) with Japanese words and included songs that Mason composed. The teacher-training school that Mason began became the Tokyo School of Music in 1890, and today, the location is occupied by the music department of the Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music in Ueno Park, Tokyo. Though the university now offers traditional Japanese music courses like koto, samisen, noh, and Japanese music history, until the late 20th century, music education was completely Western.

Children’s education of Japanese music was only presented in middle-school music appreciation courses around ten years after the conclusion of WWII. 20th century youth and workers’ choruses only performed Western repertoire and learned Western-style singing. As worldwide appreciation for cultural identity rose in the mid-20th century, Japanese music education turned back to acknowledge its traditional roots and found ways to combine the Western “robust volume of such functional, harmonized tunes [with the] quieter sounds of older, traditional music” by using the developed Westernized public-school choral tradition for an increased repertoire that now included Japanese music.

Nowadays, in public schools, music education begins at age 6 and lasts as a mandatory class until age 15 (during elementary and junior high schools). In elementary schools, music is taught as an independent subject either by the regular class teacher or by a specialized music teacher. Students learn to play recorders and sing. In junior high schools, music is taught as a separate subject, and starting from junior high, the students learn how to play traditional Japanese instruments as well. At this point in their education, 100% of students in both public and private schools have been exposed to western classical music. Music classes become optional electives at the senior high school levels, and ensembles like bands, choirs, orchestra, etc. congregate in sessions after normal school hours. The normal Japanese education timeline is: 6 years in elementary school (sho-gakko), 3 years in junior high school (chu-gakko), and 3 years in senior high school (koto-gakko). Solfege is taught with the fixed-do system, unlike most American institutions that teach movable-do.

Further schooling at a college level is subject to a performance audition and aural skills test. All music students are expected to have basic competence in piano playing. Most courses in music schools cover western classical music subjects; however, in order to receive certification as school music teachers in Japan, students are required to take courses in Japanese traditional and folk music in addition to the general music curriculum. The music education program leading to graduation with the license to teach at schools in Japan must include: solfege, vocal and instrumental ensemble (choir, instrumental ensemble, piano accompanying), conducting, music theory, composition and arrangement, Western music history, and Japanese traditional and folk music — in addition to general education degree requirements. While all these requirements don’t necessarily guarantee great results, the high standard for music educators definitely is a heartening find.

Part 4: Music in everyday life by the example of train stations and station buildings

Though much of Tokyo’s music is Western in origin, it is distributed and presented by Japanese means. It is incorporated into daily life through the city’s train stations, shopping centers and markets, individual stores, TV commercials and shows, and even household appliances (the last two will be elaborated on in a future blog post)

The train stations in Tokyo are absolutely fascinating because 1) their relative cleanliness despite the insane number of commuters, 2) the amazing shopping for gifts, clothes (Uniqlo!!!), and FOOD, and 3) the MUSIC. The music — the tunes played in the station stores as well as the train melodies to indicate train arrival or departure — always gives me a reason to smile (and forget, for a few seconds, the swelteringly humid heat of Japan in the summer).

A compilation of the JR Line melodies, if you’re curious about the sounds:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zzaYg0eHvFE

If you listen to the train music, the immediate realization is that instead of generic tones and beeps, there are real, composed melodies. It was at the Oimachi Station – Rinkai Line where I first realized that there is a reason for every train melody in every station. When I first arrived at this station, I heard the happily familiar sounds of Vivaldi’s “Spring” from Four Seasons. The Oimachi area houses the Shiki Theatre Company, the crown jewel of theatrical achievement in Japan. The meaning of Shiki? “Four Seasons.”

This drove me to research the reasons for other station melodies. At Ebisu Station – Yamanote Line, which is named after Yebisu beer and is the stop for the Yebisu Beer Museum, the train melody is “The Third Man Theme” from the classic film The Third Man. This song was used in a very famous Ebisu beer commercial and has since been associated with the company.

Other tunes are new compositions. Musicians like Takahito Sakurai work to create musical miniatures (7 seconds!) to calm the commuters and even to reduce the overall noise level of train stations. In the approximately 300 melodies that he has written, which are played in about 30 of Japan’s train stations, he searches for “presence and energy” in about the tempo of “a human heartbeat” — a description which I would assume acknowledges the natural fluctuations of tempi. Sakurai is also inspired by Japanese music traditions, including the sound of the ancient stringed koto and Zen Buddhist aesthetics, like the sound of water dripping on a rock. After the tune is written, he runs it through a computerized sound-analysis test to see how the music would mix with the sounds of a passing train; if the results are positive, the music is ready for use. He views his work as another side of Japanese miniaturization in art, in the tradition of haikus, food presentation, toys, and capsule hotels.

Sakurai’s songs, as well as the other melodies used in stations, have garnered a significant following, which shows that the train melodies are an important and valued part of Japanese culture. Albums and ringtones of train melody collections have been made to a very receptive market, and even an alarm clock equipped with these melodies has been manufactured, only to sell out of all 2,000 units priced at 5,800 yen within the first month on the market in 2002. (If you’re curious, the alarm clocks are available here.)

When I realized that the personality and culture of each stop are revealed through such a subtle but concrete way, it made me think twice about the impersonal feeling of a big city and the impression of impersonality in Japanese people. From a musical perspective, I am thrilled to see music being used in such a culturally relevant way, whether it’s classical melodies, film music, folk music, or newly-composed tunes.

On a much darker note, suicide has been a serious concern in Japan, with 2015 reports stating that an average of 65 people commit suicide every day — though the number has been dropping significantly in recent years. A number of these suicides happen at train stations, but there are several known methods of prevention. Barriers, automatic gates, TV screens showing images of nature and the ocean, and soothing blue light (which have been shown to decrease the suicide rate by 84%) are used to combat station suicides. In addition, there is a hefty fee for the families of suicide victims for causing delays in the train systems and also to discourage people from committing suicide. The most intriguing technique to me, however, is related to music and musical understanding. I was told that the keys of the station melodies are chosen based on the character and history of the stop, based on the music’s “color” and corresponding emotional response. In relation to the suicide topic, brighter major keys are used in stations with a history of suicide.

The buildings of Tokyo’s train stations are quite impressive. You can do some of the best shopping for food, clothes, and gifts right in many of the big stations. One of these huge stations is Shinjuku Station.

Another one of my favorite memories was when I was wandering through the station’s crowded underground market, looking for an afternoon snack. When I noticed that the beautiful strains of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony were floating above the noise and chaos of the crowd, I had to stop in my tracks and appreciate the initiative and the music, which somehow still seemed so fitting despite the packed environment. I might have been shocked to hear classical music in this setting, but this is actually the norm in Tokyo.

- Josephine Yang, Pianist and Violinist

Vinphonic presents:

Anime Conservatory

European Culture in Japanese Animation

A Renaissance of Classical Music

PW: MUSIK (

https://anon.click/sofay60)

Sample: What the heck is anime? (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uKi95017ut8)

Now that you’ve (hopefully) read it, I present to you a clear aural evidence of a renaissance of classical music in media, specifically ANIME, a medium I’ve grown to really really love more and more throughout the years, albeit with focus shifting from content to production. At this point I have no problem being bold enough to declare that Japanese Anime is currently the greatest medium of artistic expression (in music) on the planet right now.

Countless interpretations, arrangements and new performances of classical works can be found in this medium alone, from new upstarts to old veterans. From pantyshots and high-pitched voices (or fetish exploration), to children’s entertainment to existential philosophical drama, in the medium of anime you’ll have a high chance of listening to classical music accompanying each and every genre, played for serious drama, gravitas, tranquility, laughs or erotic tension.

I chose 60 pieces and a total of four hours with the criteria that it must not be library-paste jobs like Legend of the Galactic Heroes but must be genuine new recordings, newly arranged and performed. Regardless to say, everyone from Warsaw to local Japanse studio orchestra joins in. So far my idol Beethoven is without any doubt Anime’s classical icon, followed by Tchaikovsky. The insane amount of Beethoven homages is simply astounding, ranging from honest tribute to just plain weird: Gunslinger Girl - Ode to Joy (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l7Gu_yuyjQc&t=30s)

But that’s a given I guess, coming from the most romantic (music) country on earth (literally, they listen to romantic works in the concert hall more so than the rest of the planet combined).

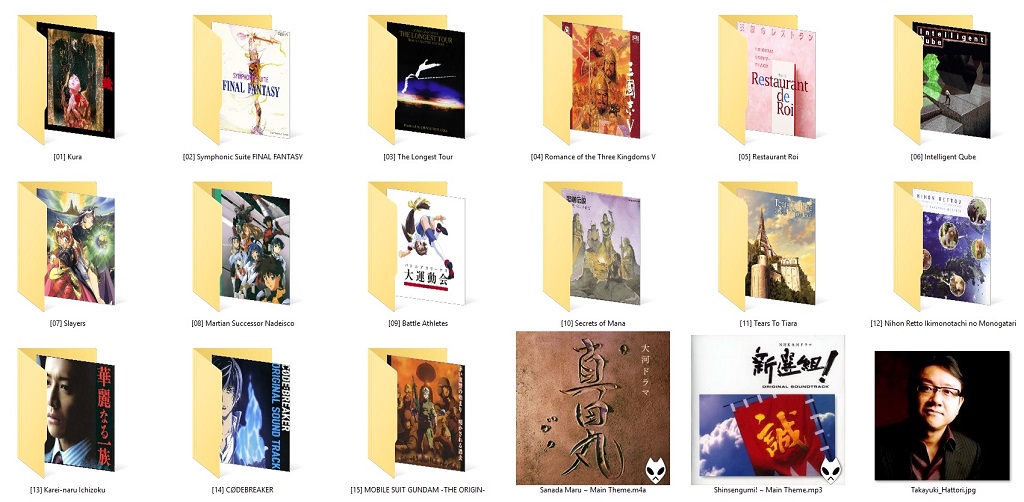

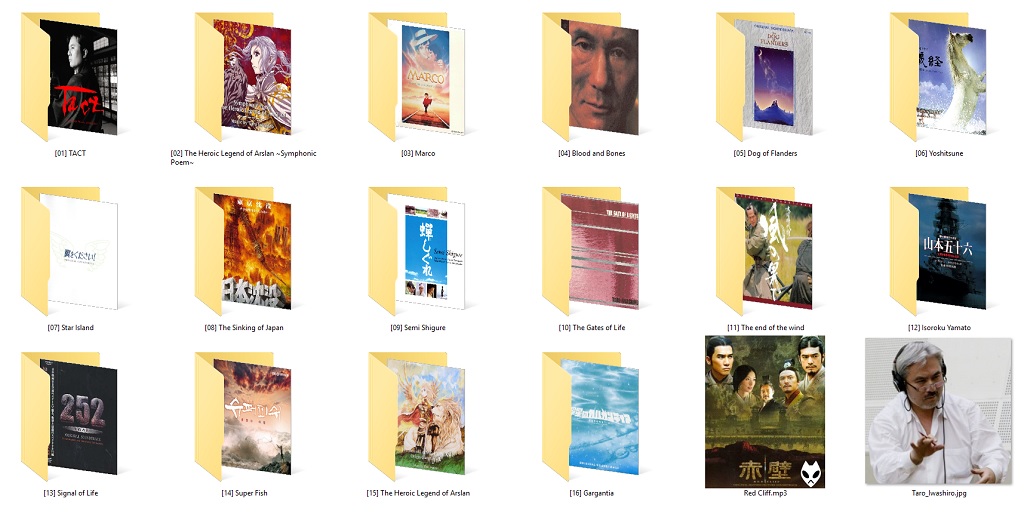

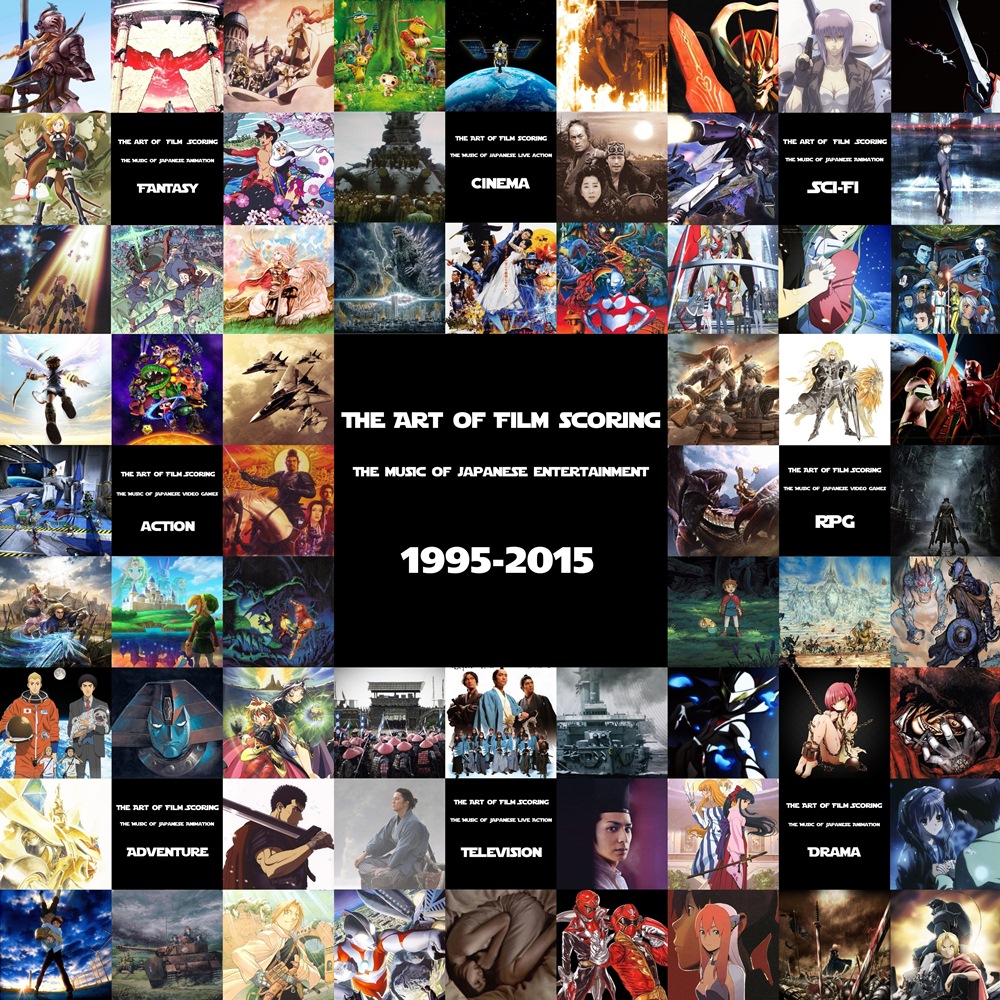

The second part focuses on entirely original classical compositions, or pieces that are more homage than interpretations, written by today’s generations of Japanese composers, that are just as much classical composers as they are film composers. An even more massive collection, clocking around six hours:

100 essential classical pieces from Japanese Anime and Games. I’ve put much thought into what to select and ultimately choose the period of 1995-2017 (I’m sorry Retro-fans, I will think of something in the future) and as a rule of thumb choose three pieces from each orchestral artist. I think what this collection/library exemplifies is an almost seamless transition from the repertoire to the original content. Just as my 2015 collection focused on Film Music, this one does on classical style, and with the medium of Anime and (to a much lesser degree) Japanese Games it was very easy to quickly assemble a collection of the same magnitude as 2015.

I think you would be hard-pressed to find a piece here with inherently Japanese flavor, this is pretty much European cultural heritage par excellence and the medium of Anime deserves far more respect, attention and cultural recognition worldwide for the wonderful things it does, most of all keeping European culture alive, from the beautiful romanticized version of Venice to the Imperial splendor of Paris to 60’s Britain. I’m just amazed just how much European cultural influence there is, from setting to fashion to music. And all are done with 100% attention to detail:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_tFOJFyTl1U&t=43s

Nonetheless, it all continues ever strong, just last week we had a delicious little string arrangement of Strauss Danube Waltz and on the other side of the spectrum a cheap version of Dance of the Knights from your average ecchi series.

Also leave it to the Japanese to make classical style synonymous with eroticism = just like my ancient Greeks. And oh boy, they really jumped the shark in that regard:

A Pantsu Odyssey (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xr4qhlkrvus)

And wait till you get to Kizu III, which has basically a ..... scene underscored by opera.

But back to point, classical music continues to be ever strong in anime, just take this recent trailer of a Japanese mobile app:

Shadowverse - Wonderland Dreams (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XG79Bu8fTUU)

Take on Me (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sqoYr68QgSk) (and this one too I guess)

Take note just how much you see is inspired by European Folklore and Culture, from the art to the music while still maintaining an original identity and unique artistic “Japanese” voice.

Next season is already offering us a big title with Vatican Miracle Examiner (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Odbzhf3TwFU)

And classical music is also used in various commercials and trailers: Beethoven - Symphony No. 5 (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cjx_GyJbhsU&t=10s)

Not to mention the extraordinary classical inspired music you can find in the niche within a niche Japanese anime/game-indie scene, from solo artists to collaborations:

SANCTUS (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgZ4YlzwUnM) (Baroque lives!!!)

And how about taking a complete random pick of a fresh anime newcomer…. Ryo Kawasaki it is… do you want to know his biggest classical idol?!:

Brahms - Orchestra Arrange (

https://soundcloud.com/ryo-kawasaki/gs2kqpkfuty5)

And this wonderful little project was brought to my attention: Animation project for Vivaldi's four seasons (

http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/daily-briefs/2017-06-15/animation-project-for-vivaldi-the-four-seasons-to-also-open-crowdfunding-on-kickstarter/.117544)

But also not the first time an Anime music video has been made for a classical piece: Tchaikovsky - Manfred (Music Video) (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SB56qFLo9og&t=1m41s)

Various openings from anime projects illustrate this point quite well also:

Cras numcqam scire (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_WjZuC6IElY) (this show has some great self-contained episodes)

Elfenlied - Lilium (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KokfYulpSqA) (One of the most beautiful anime ops ever made)

Aria the Arietta (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsUm6u8qXAk)(Aria is one of the greatest anime experiences I ever had)

Spice and Wolf (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MN_WgwEmRaw) (the show's also a gem)

Berserk (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhEzb-FCFnk) (still can't fathom how abyssmal the current TV adaption is)

Broken Blade - Fate (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cB8_w7XdW_I)

Kado - The Right Answer (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iyT2wbvXytk)

Lupin III: Italiano (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvaosZlQqrY) (I liked it a lot)

ACCA 13 (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pITNm95Sd1k) (I liked that show a lot as well)

Yuri on Ice (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORDXWrL5EuQ)

And for the big finish, how about a Japanese live-action adaption of a classical music manga, with an equally dedicted anime version: Tchaikovsky - 1812 (Nodame vers.) (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFKa9DouO8Y&t=1m27s)[/CENTER]

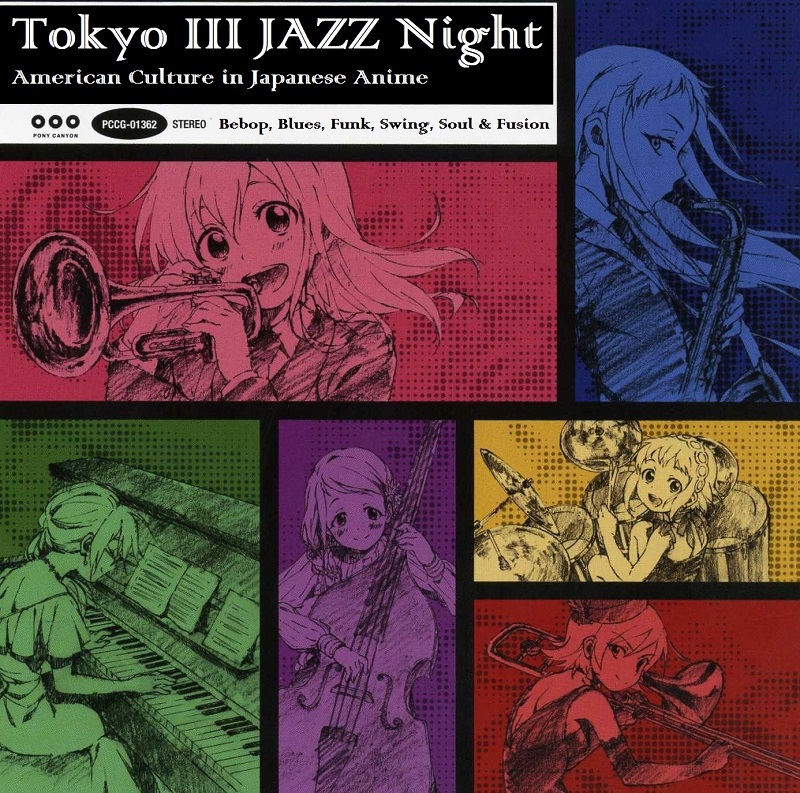

Now moving on to the second chapter, American Culture in Japanse Anime:

„I don’t care what color they are. As long as they can play the music it’s supposed to be played and swing, they could have purple skin for all I care” – Miles Davis, Jazz Legend.

The second major collection is about American culture, particularly Jazz culture and what made it great in the past and kicking off the rails in Japan right now! Again, here’s a little essay I would recommend before diving in:

Tokyo’s Thriving Jazz Scene

A few years ago a friend took me to Samurai, a jazz bar in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district whose owner, a haiku poet, stood behind the bar surrounded by thousands of maneki neko—smiling, waving cat figurines. He had a primitive video camera trained on the sleeve of the record album he was playing, and he projected that image onto the wall. Samurai had its own quirks, but it wasn’t an unusual type of place: The jazz bar and its cousin, the jazz kissaten, a coffee shop focused on jazz, are shrines to recorded music, dreamlands for high-fidelity obsessives. They offer a kind of jazz experience based on pure appreciation of the act of listening.

In Tokyo I track down James Catchpole, an American expat and jazz expert who goes by the very Japanese-sounding nickname of Mr. OK Jazz, to understand what’s happening right now to Japanese jazz culture. “When these kissa started back in the ’50s and ’60s, Tokyo apartments were too small to play music in,” Catchpole says. “Imported records were really expensive. Jazz kissa were the only places in the city where fans could listen to the music they loved.” The coffee shops became hideaways where jazz lovers could relax, hear new records and learn about trends like free jazz from others who knew the music well. In the ’60s, when jazz was allied with Japanese university counterculture, jazz kissa became organizing centers for the student protests that rocked Japan. But of course Japanese people no longer need to visit a bar or caf� to listen to recorded jazz. “Are jazz kissa going to survive?” I ask Catchpole.

“Go to Kissa Sakaiki and find out,” he says.

Tokyo’s tiny caf�s, bars and restaurants are notoriously difficult to locate. Even with a GPS-equipped iPhone, a print atlas and the help of police guarding a nearby embassy, I spend half an hour wandering the back streets of Yotsuya, a residential Tokyo neighborhood not far from Shinjuku, before I turn the corner and see the discreet sign for Sakaiki.

What makes places like Sakaiki or the Bob Dylan bar survive and sometimes prosper is the fragmentation of bar, caf� and restaurant culture in Tokyo. An eight-seat pub stands out in New York as supremely small, yet in Tokyo there are at least three nightlife neighborhoods consisting almost entirely of eight-seat bars. You don’t need many fans of whatever it is you’re into to support a bar, caf� or restaurant devoted to that obsession.

When I enter Sakaiki, owner Fumito Fukuchi, wearing a gray newsboy cap turned backward, waves me to the bar. Seated next to me is a Swedish free-jazz clarinetist speaking English to a group of Japanese. I tell Fukuchi that Mr. OK Jazz sent me. He nods a welcome and serves me a cold beer. The place is small, warm and gently lit, with a green-shaded banker’s lamp shining on the album cover of the record he’s playing. I ask Fukuchi how he came to run Sakaiki.

“I was a salaryman working in IT until 2007,” he tells me, as he cleans, inspects and preps the next record in his rotation. “Jazz kissa were my hobby,” he says, leading me to a coffee table covered in matchboxes from the jazz kissa of Tokyo. He picks up a matchbook that reads, “Eagle.” “This is the first one I ever visited. It’s right here in Yotsuya. I read the owner’s book about jazz when I was a teenager in Hokkaido. As soon as I came to Tokyo, I headed for Eagle.” Many of the matchbooks Fukuchi flips through are from jazz kissa that have long been closed. And all the other jazz kissa he knows of in Tokyo, he tells me, are run by men a decade or two older than he is—and he’s 41.

The obvious question is why go out of your way to hear recorded music with other people when technology has made it easy to listen alone? The answer comes to me as I look around the room at the people brought together by the music Sakaiki has collected: International jazz musicians, local workers and jazz fans from all over the city are here because they appreciate the act of listening to a record together. It’s a pleasure that the Walkman or iTunes just can’t provide.

By Tom Downey, SMITHSONIAN MAGAZIN

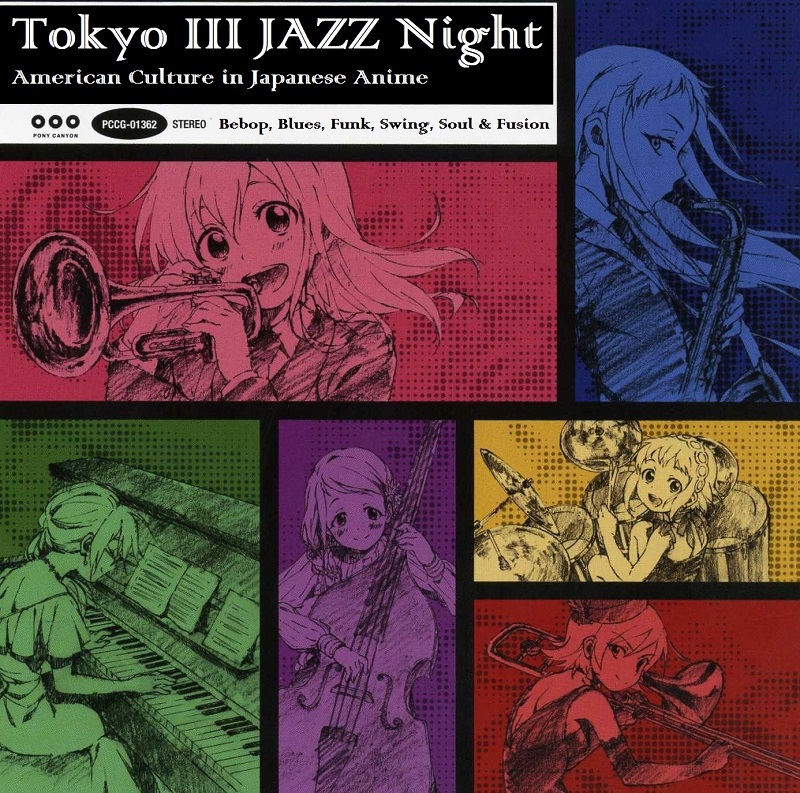

Vinphonic presents

Tokyo III Jazz Night

American Culture in Japanese Anime

A Renaissance of Jazz, Funk and Rock&Roll

PW: SwingAllNight (

https://anon.click/lakuv37)

Sample: What the heck is Anime Jazz? (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nEfWNEMeSc)

American culture (Golden 20s, Jazz, Broadway, Old Disney and Rock&Roll) certainly leaved a mark in Japan. But it’s not just music, the fashion, cuisine and flair of the ideal golden Americana lives on in various media and daily Japanese life. Cowboy Bebop and Space Dandy were so adored by especially Americans because it represents this distilled essence of American culture. And it continues to this day with projects like Baccano to 91 Days. It’s no surprise we are hearing so much Jazz every anime season.

Here I’ve selected 60 tracks of the best of various Jazz styles and genres we can hear aplenty in Japanese Animation. I think this collection examplifies the “coolness” factor I believe Anime holds for many young Japanse (and western) music artists and why it is currently the greatest visual medium for expression and creative (musical) talent. Not that Iwasaki wouldn’t be example enough. Everything is in there from Bebop to Gospel, and all so wonderfully out of time, all styles and cultures accumulating, for sexual innuendos, smooth criminals and shady bars. And it all got that swing! A renaissance of Jazz in all flavors, under one banner: Anime Jazz. My favorite kind of Jazz.

And with numerous indie groups and bar scenes in Tokyo, countless Big Band and Jazz Band tributes to Anime and Games and of course the upcoming “months of Jazz” we can be sure it has secured a special place in Japanese culture:

I’LL BE YOUR 1-UP GIRL (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbR_pCRPDTg)

SING SING SING (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGGwyb0d0Y8) (now this is the Hayashi I like)

Kakegurui (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7m9EC_iuJmw) (I sense real artistry from one or two composer from their unit so lets see how it will end up)

Princess Principal (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nW3skpmMMzs) (even Kajiura does it!)

The “rose-colored” America can be found in numerous anime projects from Cowboy Bebop to Baccano to Love Live to Blood Blockade Battlefront. And if you want to fondly remember the heights of american“pop culture”, there’s no one better to listen to than Shiro Sagisu (his songbooks are great pop works if nothing else). Occasionally there’s also a huge amount of class inspired by that ideal Americana you find in the occasional anime/game project:

Cowboy Bebop - Ask DNA (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofSLCFxJ8Jo) (very good movie)

Baccano - Guns & Roses (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOZ1hsb8smQ) (really liked the show)

Onihei (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RWjqvLEoXWg) (didn't hold my interest for long)

Death Parade - Flyers (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DwbXmr70C0) (interesting show but not as strong as the OP implies)

Rakugo Shinjuu (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K28Lcc-MdJs) (good show)

Garo - Bloody Brother (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aziPdaZAbs)

Persona 5 (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lswcZg7BH2M) (aka greatest JRPG in years)

Persona 4: Dance! (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3jw89oIjmQ)

Space Dandy - Viva Namida (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI9aye8uTCk)

King Gainer (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bPKULArJNCQ) (one of the greatest anime openings ever made)

Samurai Champloo (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OuRajFzMYI) (some pretty good episodes)

Not to mention how a children’s show occasionally turns into Broadway:

Heartcatch Precure - Tomorrow Song (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnXjWaZaFMg)

Princess Precure - Dreamroad to the Future (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uUfLt7pB6t0)

Precure all stars -Haru no Carnival (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxuTiW5_3b0)

And I don't think I have to point out which scene this is inspired by:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eh_NE4YF9Mg&t=33s

And here’s a sample from the thousands of Jazz fan albums floating around:

Moe Jazz (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3o1MW3QoQME&index=3&list=PLJIhLbDdr8NNJTCNy2E3PXxySkz7TK0MW) (not for the faint of heart)

Touhou Jazz (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkL3fSYBOf8&index=8&list=PLJIhLbDdr8NNJTCNy2E3PXxySkz7TK0MW)

And, for the big finish, how about some animated Jazz Session (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ounHSQvu9Yc)[/CENTER]

So that about does it, but before I leave you with much amazing music to marvel at, especially when its compiled and presented this way, I think these poignant words from the full second essay need to be highlighted:

“Part of what’s going on (in Tokyo) is simply the globalization of taste, culture, cuisine and the way that, in the modern world, you can get almost anything everywhere. But Japanese Americana and Japanese European Style is more than that. There’s a special way that the Japanese sensibility has focused on what is great, distinctive and worthy of protection in American and European culture, even when Americans or Europeans have not realized the same thing. It isn’t a passing fad. It’s a long-standing part of Japanese culture, and, come to think of it, as more Americans and Europeans are exposed to products, music or visual art revived or reinterpreted by Japanese designers, artists and musicians, the aesthetic is essentially becoming part of American and European culture, too. If you ever wonder which of the reigning American and European tastes, sounds, designs or styles will last into the future, there’s no better place to answer that question than in the stores and restaurants, the bars and studios, the television and computer screens of Japan. They often know us better than we know ourselves.”