wimpel69

05-08-2014, 09:56 AM

THE LINKS ARE NO LONGER AVAILABLE.

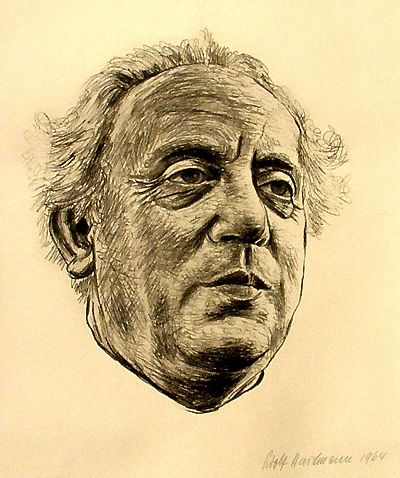

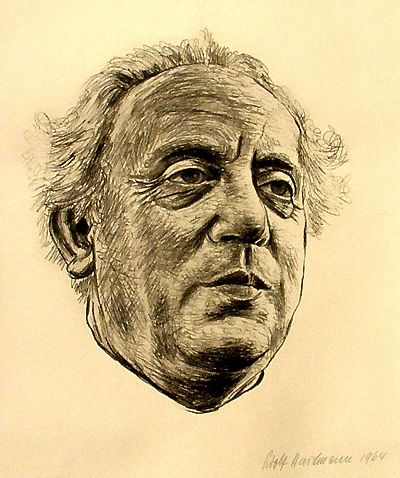

Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905-1963) has been proclaimed by supporters the finest German symphonist

since Johannes Brahms, although he is a somewhat controversial figure among the more open-minded. Using

Baroque, jazz and various other musical elements, he forged an eclectic style that divulged the influence of Reger,

Stravinsky and Hindemith. He was versatile, producing operas, symphonies, various orchestral scores, chamber

and choral music, and solo works for piano and violin.

Hartmann's first serious studies began in 1924 at Munich's Akademie der Tonkunst, chief among his teachers

being Joseph Haas. After five years there he moved on to studies with conductor Hermann Scherchen and, later,

with Anton Webern. By 1933, owing to the success of his Concerto for Trumpet and Wind Ensemble, he was gaining

considerable recognition. Around this time, Hartmann adopted a firm anti-Nazi stance, avoiding military service and,

some say, actively defying government policies.

One of his brothers was known to have distributed anti-Nazi leaflets, and while Hartmann's wife claimed her husband's

resistance was passive, others reported that the composer helped political prisoners across the border. Whatever the level

of his opposition to Hitler, he was harassed by the Nazis and his music was not played in Germany until after the war.

Yet, he remained active in the field of composition throughout the Nazi reign, producing many scores, large and small,

like the symphonic poem Miserae (1934), the Concerto funebre (1939), Sinfonia Tragica (1940-43),

and the dark Symphony No.2 (1945-46). Following the war Hartmann established a concert series in Munich

called Musica Viva. He also took on the post as dramaturge at the Munich State Opera. He garnered a string of

composition prizes, including the Munich music prize (1949) and ISCM Schoenberg Medal (1954).

In the final decade of his life, Hartmann turned to the influence of Boris Blacher, using his ideas concerning changeable

meter, as exhibited in works like Hartmann's 1953 Concerto for Piano and 1955 Concerto for Viola. His reputation

grew in the 1950s, reaching across the Atlantic: Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered his

Symphony No.7 (1957-58). Still, Hartmann never quite reached the front rank of 20th century composers, despite

the respect he had gained among conductors and musicians alike. He died of stomach cancer at the age of 58.

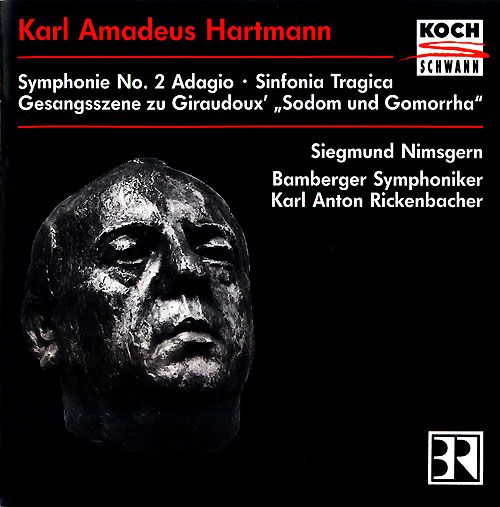

Music Composed by

Karl-Amadeus Hartmann

Played by the

Bamberg Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by

Ingo Metzmacher

Karl Anton Rickenbacher

"This is not the first complete cycle of the Hartmann symphonies. That honour rests with Wergo who issued

them on four CDs in 1989. Before that the Wergo recordings had appeared in an LP boxed set in 1980. The CDs

were designated AAD with the recordings being studio tapes from Bavarian Radio variously conducted by Macal,

Rieger, Leitner and predominantly Kubelik. The EMI set derives from full digital recordings made by one orchestra

and conductor. Interestingly Bavarian Radio are behind the cycle but this time the Bamberg orchestra is used

rather than Bavarian Radio forces.

If you do not know Hartmann's symphonies then you need to think in terms of Mahler�s Sixth filtered through

Berg and the Stravinsky of Oedipus Rex; maybe the Symphony of Psalms.

The phantasmagorical First Symphony is greatly enhanced in its cataclysmic despairing impact by the superb

contralto of Cornelia Kallisch who enunciates each word of the Whitman poems with rare intelligence and

accuracy. Comparing the Rieger version on Wergo we encounter the very best of analogue technology with spot-

lit microphone placement of considerable power. Doris Soffel is in much the same league as Kallisch but is

more closely recorded. It has to be said that even this close-up positioning does no disservice to Soffel's voice.

The Third Symphony sounds more strikingly powerful in the Wergo recording (conducted by Leitner) but

closer examination prompts a recommendation for the EMI whose wide dynamic range from whispered

Bachian cantabile to clamorous protest in the massive adagio is rendered superbly by the new digital recording.

After the 35 minutes of the Third Symphony hearing the quarter hour Second Symphony in all its glowing

luminosity and with its references to the sinister woodwind writing in the Rite of Spring, is almost a relaxation.

While the EMI lacks the concert depth and immediacy of the Wergo it is a more natural balance. If you want

spectacular rather than natural then you opt for Wergo but dynamic range is rendered with greater fidelity by EMI.

The half hour Fourth Symphony is intensely put across by Kubelik who on Wergo also conducts numbers 5

and 6 and the Gesangs-Szene the latter not included in the Metzmacher. EMI stick to the symphonies and

nothing but the symphonies. Metzmacher is in not quite the same league of intensity as Kubelik but the

recording has plenty of heft as a comparison of the two versions of the allegro di molto second movement shows.

When it comes to the bubbly Pulcinella-accented Fifth Symphony with its scherzo looking back seventeen years

to the finale of Shostakovich's First Piano Concerto, honours are divided pretty equally. Close-up recording

placement is typical of the whole Wergo cycle making a really immediate impact on the listener.

The Sixth Symphony is one of the most powerful symphonic utterances of the 1950s. A hefty adagio is followed

by a manic Toccata variata which runs out of hand even faster with Metzmacher than with Kubelik.

From the Sixth Symphony onwards all the symphonies were in two movements. The Seventh was first performed

in 1959 having been written over the previous three years. It is soured, Bergian, the zenith of clarity and the

avoidance of orchestral congestion. Metzmacher has the usual advantage of totally silent surfaces whereas Macal

(in an unaccustomed role in 20th century repertoire) labours with the analogue hiss which seems to be slightly

more noticeable in this case. The EMI bands the second section (scherzoso virtuoso) of the last movement

separately where the Wergo does not.

The Eighth is Hartmann's most extreme symphony. It is soured in the avant-garde episodic kaleidoscopic stream.

Brilliantly recorded in the Wergo version, the players put it across with an almost death-defying singleness of

purpose; so do Metzmacher and his orchestra. Metzmacher makes more of the poetry of the work -

and there is poetry there."

Musicweb

Source: EMI + Koch Schwann CDs (my rips!)

Format: FLAC(RAR), DDD Stereo, Level: -5

File Sizes: 813 MB + 275 MB

THE LINKS ARE NO LONGER AVAILABLE.

Enjoy! Don't share! Buy the originals! :)

Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905-1963) has been proclaimed by supporters the finest German symphonist

since Johannes Brahms, although he is a somewhat controversial figure among the more open-minded. Using

Baroque, jazz and various other musical elements, he forged an eclectic style that divulged the influence of Reger,

Stravinsky and Hindemith. He was versatile, producing operas, symphonies, various orchestral scores, chamber

and choral music, and solo works for piano and violin.

Hartmann's first serious studies began in 1924 at Munich's Akademie der Tonkunst, chief among his teachers

being Joseph Haas. After five years there he moved on to studies with conductor Hermann Scherchen and, later,

with Anton Webern. By 1933, owing to the success of his Concerto for Trumpet and Wind Ensemble, he was gaining

considerable recognition. Around this time, Hartmann adopted a firm anti-Nazi stance, avoiding military service and,

some say, actively defying government policies.

One of his brothers was known to have distributed anti-Nazi leaflets, and while Hartmann's wife claimed her husband's

resistance was passive, others reported that the composer helped political prisoners across the border. Whatever the level

of his opposition to Hitler, he was harassed by the Nazis and his music was not played in Germany until after the war.

Yet, he remained active in the field of composition throughout the Nazi reign, producing many scores, large and small,

like the symphonic poem Miserae (1934), the Concerto funebre (1939), Sinfonia Tragica (1940-43),

and the dark Symphony No.2 (1945-46). Following the war Hartmann established a concert series in Munich

called Musica Viva. He also took on the post as dramaturge at the Munich State Opera. He garnered a string of

composition prizes, including the Munich music prize (1949) and ISCM Schoenberg Medal (1954).

In the final decade of his life, Hartmann turned to the influence of Boris Blacher, using his ideas concerning changeable

meter, as exhibited in works like Hartmann's 1953 Concerto for Piano and 1955 Concerto for Viola. His reputation

grew in the 1950s, reaching across the Atlantic: Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered his

Symphony No.7 (1957-58). Still, Hartmann never quite reached the front rank of 20th century composers, despite

the respect he had gained among conductors and musicians alike. He died of stomach cancer at the age of 58.

Music Composed by

Karl-Amadeus Hartmann

Played by the

Bamberg Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by

Ingo Metzmacher

Karl Anton Rickenbacher

"This is not the first complete cycle of the Hartmann symphonies. That honour rests with Wergo who issued

them on four CDs in 1989. Before that the Wergo recordings had appeared in an LP boxed set in 1980. The CDs

were designated AAD with the recordings being studio tapes from Bavarian Radio variously conducted by Macal,

Rieger, Leitner and predominantly Kubelik. The EMI set derives from full digital recordings made by one orchestra

and conductor. Interestingly Bavarian Radio are behind the cycle but this time the Bamberg orchestra is used

rather than Bavarian Radio forces.

If you do not know Hartmann's symphonies then you need to think in terms of Mahler�s Sixth filtered through

Berg and the Stravinsky of Oedipus Rex; maybe the Symphony of Psalms.

The phantasmagorical First Symphony is greatly enhanced in its cataclysmic despairing impact by the superb

contralto of Cornelia Kallisch who enunciates each word of the Whitman poems with rare intelligence and

accuracy. Comparing the Rieger version on Wergo we encounter the very best of analogue technology with spot-

lit microphone placement of considerable power. Doris Soffel is in much the same league as Kallisch but is

more closely recorded. It has to be said that even this close-up positioning does no disservice to Soffel's voice.

The Third Symphony sounds more strikingly powerful in the Wergo recording (conducted by Leitner) but

closer examination prompts a recommendation for the EMI whose wide dynamic range from whispered

Bachian cantabile to clamorous protest in the massive adagio is rendered superbly by the new digital recording.

After the 35 minutes of the Third Symphony hearing the quarter hour Second Symphony in all its glowing

luminosity and with its references to the sinister woodwind writing in the Rite of Spring, is almost a relaxation.

While the EMI lacks the concert depth and immediacy of the Wergo it is a more natural balance. If you want

spectacular rather than natural then you opt for Wergo but dynamic range is rendered with greater fidelity by EMI.

The half hour Fourth Symphony is intensely put across by Kubelik who on Wergo also conducts numbers 5

and 6 and the Gesangs-Szene the latter not included in the Metzmacher. EMI stick to the symphonies and

nothing but the symphonies. Metzmacher is in not quite the same league of intensity as Kubelik but the

recording has plenty of heft as a comparison of the two versions of the allegro di molto second movement shows.

When it comes to the bubbly Pulcinella-accented Fifth Symphony with its scherzo looking back seventeen years

to the finale of Shostakovich's First Piano Concerto, honours are divided pretty equally. Close-up recording

placement is typical of the whole Wergo cycle making a really immediate impact on the listener.

The Sixth Symphony is one of the most powerful symphonic utterances of the 1950s. A hefty adagio is followed

by a manic Toccata variata which runs out of hand even faster with Metzmacher than with Kubelik.

From the Sixth Symphony onwards all the symphonies were in two movements. The Seventh was first performed

in 1959 having been written over the previous three years. It is soured, Bergian, the zenith of clarity and the

avoidance of orchestral congestion. Metzmacher has the usual advantage of totally silent surfaces whereas Macal

(in an unaccustomed role in 20th century repertoire) labours with the analogue hiss which seems to be slightly

more noticeable in this case. The EMI bands the second section (scherzoso virtuoso) of the last movement

separately where the Wergo does not.

The Eighth is Hartmann's most extreme symphony. It is soured in the avant-garde episodic kaleidoscopic stream.

Brilliantly recorded in the Wergo version, the players put it across with an almost death-defying singleness of

purpose; so do Metzmacher and his orchestra. Metzmacher makes more of the poetry of the work -

and there is poetry there."

Musicweb

Source: EMI + Koch Schwann CDs (my rips!)

Format: FLAC(RAR), DDD Stereo, Level: -5

File Sizes: 813 MB + 275 MB

THE LINKS ARE NO LONGER AVAILABLE.

Enjoy! Don't share! Buy the originals! :)