wimpel69

04-15-2014, 08:35 AM

The sharing period for these albums has ended. No more requests, and no re-ups of my material please!

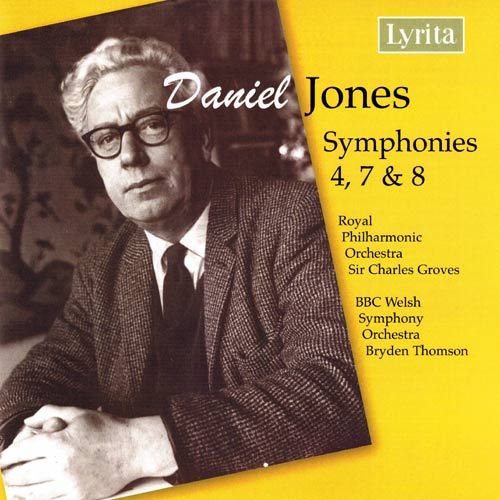

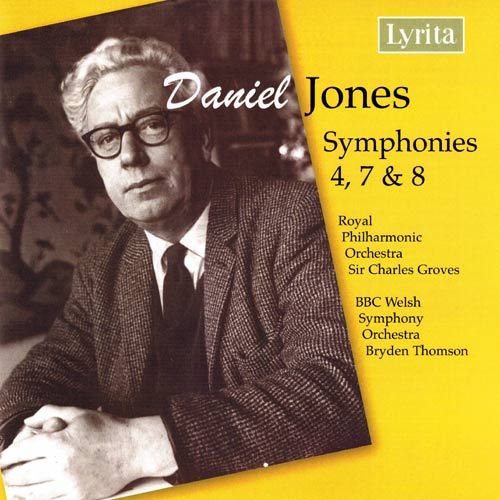

Daniel Jenkyn Jones (1912-1993) is often regarded as having been the greatest Welsh composer. His music is marked

by traditional form, some adherence to tonality, and complex meters. His most notable works are his 13 symphonies (in 12

different keys) and eight string quartets. When Jones was young, his family moved to Swansea. His father and brother both

composed; his mother was accomplished at needlework, which, he said, gave him a love for intricate recurring patterns in a design.

He began to compose while he was still a child. Jones took his bachelor's and master's degrees in English Literature at Swansea

University in 1934 and 1939, but he had already won recognition as a composer by receiving the Mendelssohn Scholarship in 1935.

(He had submitted works he wrote even before his college years). He used the scholarship for study travels to Czechoslovakia,

Holland, France, and Germany. His trips to Europe were partly to experience the various cultures there, partly to expand his

talent for languages, and partly to experience music. In the meanwhile, he became part of an artistic group based in Swansea

that included poets Dylan Thomas and Vernon Watkins and the painters Fred Janes and Kerry Richards.

He attended the Royal Academy of Music from 1939, studying viola, horn, conducting (with Henry Wood), and composition.

His interest in numbers and complex patterns led him to begin using recurring metric shifts of a pattern of different measure-

lengths that would repeat. This allowed him to create melodies of rhythmic ambiguity but with an underlying symmetry and

organization. One source of his metrical patterns was nature: he constantly sought to recognize patterns in the environment,

and he kept a microscope so he could look for patterns in plants.

In World War II, the Army recognized his talents as a linguist and cryptographer, and sent him to the top-secret code-breaking

establishment at Bletchley Park, where he specialized in Russian, Rumanian, and Japanese intercepts and documents. Of

necessity he did not undertake any composition -- there was not time for that -- but was able to think about musical

structures and ideas. He said these years enabled him to assimilate all he had learned about music in his travels and studies.

After the war, Jones moved for a year to Cornwall, mostly intending to sketch out ideas and develop his mature style.

He destroyed or embargoed the music he had written before the War. His first major compositions emerged from the

year in Cornwall: his First Symphony (1945) and First String Quartet (1946). After that he returned to Swansea,

where he lived for the rest of his life. Despite not entering the London musical life, he did see his career develop after

he won the Royal Philharmonic Prize for an orchestral work, Prologue, in 1950.

He came to further attention with his score for a famous radio interpretation of Dylan Thomas' Under Milk Wood, which

won the Italia Prize in 1954. After Thomas' death Jones became the trustee of his estate and edited the edition of Thomas'

complete poems. He also wrote one of the first notable biographies of the poet, My Friend Dylan Thomas. Jones has said

that subconsciously there is always an element of Welshness to his music, though he does not often use folk material.

Most of his commissions came from Welsh festivals and organizations.

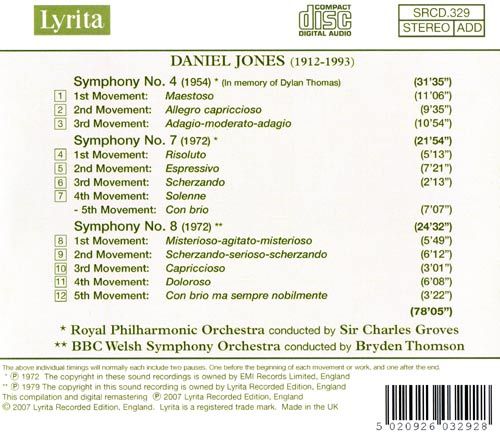

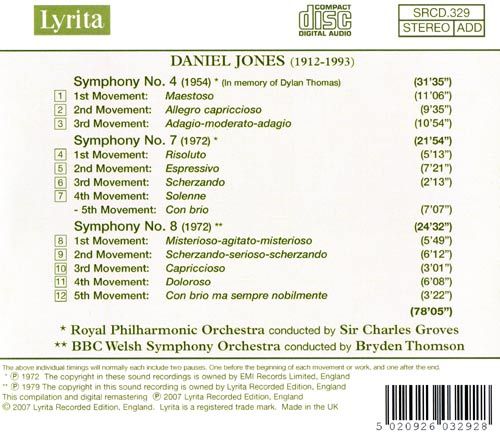

Music Composed by

Daniel Jones

Played by the

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra

With the

Welsh National Opera Chorus

Conducted by

Sir Charles Groves

Bryden Thomson

"There has been something of a revival of interest in Daniel Jones's music lately, and I was glad of the

opportunity that this reissue provides to catch up with it. His language is immediately striking: dark,

craggy, strongly dramatic and powerfully vehement. It frowns a good deal, and he has a way of what

one might call 'block orchestration', whole groups or families of instruments being used like thickly

applied pigments, that can lead to densely full textures at times. It is somehow characteristic of him

that in The Country beyond the Stars, a brief cantata on texts by Henry Vaughan, he should choose to

set "The Morning Watch" ("0 joyes! Infinite sweetness! With what flowres and shoots of glory my soul

breakes and buds!") with very full textures and rather earthbound dotted rhythms, while his refusal to

indulge in mere picturesque onomatopoeia in "The Bird" ("The Turtle then in Palm-trees mourns, while

Owls and Satyrs howl") is somehow both admirable in its earnestness and disappointing.

Once on his wavelength, however, there is much to admire here: the tensely expressive lyricism that

Jones can distil from brooding darkness, the sheer resourceful skill of his thematic working, the passionate

eloquence that is sometimes won from this. He is, it seems to me, something of a hit-and-miss composer:

both the Ninth Symphony and the cantata begin well (a striking group of pithy ideas, absorbingly

discussed; a warmly melodious, amply singable hymn) but end disappointingly (the symphony with

what sounds like a sonata movement that never gets beyond the exposition, the cantata with a heavy-

limbed fugue, a glumly inadequate response to Vaughan's ecstatic jubilance). But the dark, urgent

drama of the Sixth Symphony, the lift-off that Jones's brusquely springy rhythms can attain, above

all a sort of hard-won sustained intensity of utterance (the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony is

a good example) make him a genuine symphonist, one whose wrestlings with the form are absorbing

even when they don't quite come off. The performances are excellent throughout; the recordings are

beginning to sound their age (a patch or two of glare) but are perfectly serviceable."

Gramophone

The sharing period for these albums has ended. No more requests, and no re-ups of my material please!

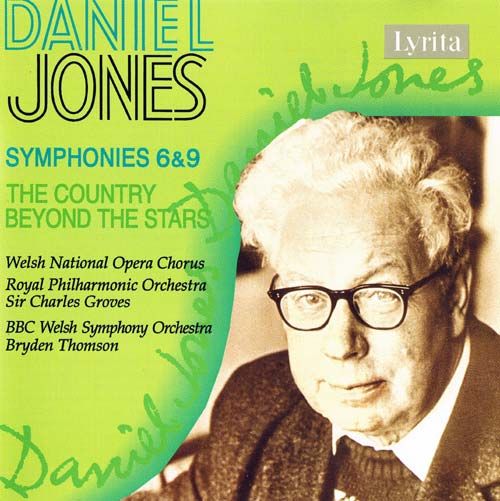

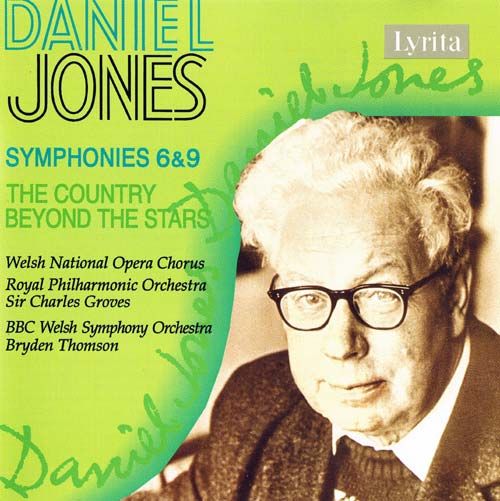

Daniel Jenkyn Jones (1912-1993) is often regarded as having been the greatest Welsh composer. His music is marked

by traditional form, some adherence to tonality, and complex meters. His most notable works are his 13 symphonies (in 12

different keys) and eight string quartets. When Jones was young, his family moved to Swansea. His father and brother both

composed; his mother was accomplished at needlework, which, he said, gave him a love for intricate recurring patterns in a design.

He began to compose while he was still a child. Jones took his bachelor's and master's degrees in English Literature at Swansea

University in 1934 and 1939, but he had already won recognition as a composer by receiving the Mendelssohn Scholarship in 1935.

(He had submitted works he wrote even before his college years). He used the scholarship for study travels to Czechoslovakia,

Holland, France, and Germany. His trips to Europe were partly to experience the various cultures there, partly to expand his

talent for languages, and partly to experience music. In the meanwhile, he became part of an artistic group based in Swansea

that included poets Dylan Thomas and Vernon Watkins and the painters Fred Janes and Kerry Richards.

He attended the Royal Academy of Music from 1939, studying viola, horn, conducting (with Henry Wood), and composition.

His interest in numbers and complex patterns led him to begin using recurring metric shifts of a pattern of different measure-

lengths that would repeat. This allowed him to create melodies of rhythmic ambiguity but with an underlying symmetry and

organization. One source of his metrical patterns was nature: he constantly sought to recognize patterns in the environment,

and he kept a microscope so he could look for patterns in plants.

In World War II, the Army recognized his talents as a linguist and cryptographer, and sent him to the top-secret code-breaking

establishment at Bletchley Park, where he specialized in Russian, Rumanian, and Japanese intercepts and documents. Of

necessity he did not undertake any composition -- there was not time for that -- but was able to think about musical

structures and ideas. He said these years enabled him to assimilate all he had learned about music in his travels and studies.

After the war, Jones moved for a year to Cornwall, mostly intending to sketch out ideas and develop his mature style.

He destroyed or embargoed the music he had written before the War. His first major compositions emerged from the

year in Cornwall: his First Symphony (1945) and First String Quartet (1946). After that he returned to Swansea,

where he lived for the rest of his life. Despite not entering the London musical life, he did see his career develop after

he won the Royal Philharmonic Prize for an orchestral work, Prologue, in 1950.

He came to further attention with his score for a famous radio interpretation of Dylan Thomas' Under Milk Wood, which

won the Italia Prize in 1954. After Thomas' death Jones became the trustee of his estate and edited the edition of Thomas'

complete poems. He also wrote one of the first notable biographies of the poet, My Friend Dylan Thomas. Jones has said

that subconsciously there is always an element of Welshness to his music, though he does not often use folk material.

Most of his commissions came from Welsh festivals and organizations.

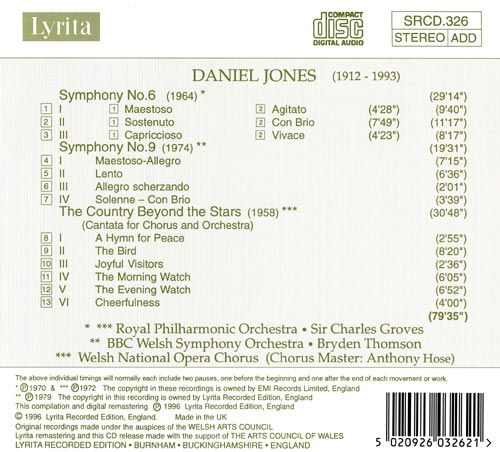

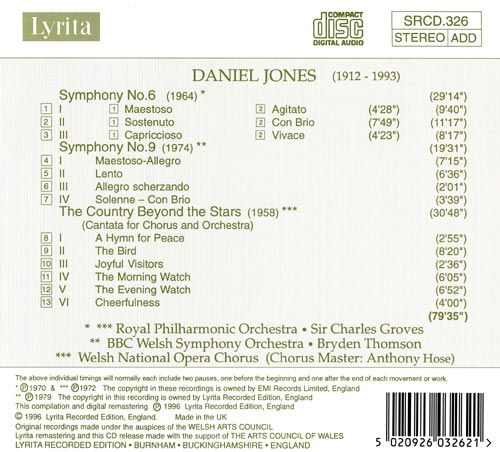

Music Composed by

Daniel Jones

Played by the

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra

With the

Welsh National Opera Chorus

Conducted by

Sir Charles Groves

Bryden Thomson

"There has been something of a revival of interest in Daniel Jones's music lately, and I was glad of the

opportunity that this reissue provides to catch up with it. His language is immediately striking: dark,

craggy, strongly dramatic and powerfully vehement. It frowns a good deal, and he has a way of what

one might call 'block orchestration', whole groups or families of instruments being used like thickly

applied pigments, that can lead to densely full textures at times. It is somehow characteristic of him

that in The Country beyond the Stars, a brief cantata on texts by Henry Vaughan, he should choose to

set "The Morning Watch" ("0 joyes! Infinite sweetness! With what flowres and shoots of glory my soul

breakes and buds!") with very full textures and rather earthbound dotted rhythms, while his refusal to

indulge in mere picturesque onomatopoeia in "The Bird" ("The Turtle then in Palm-trees mourns, while

Owls and Satyrs howl") is somehow both admirable in its earnestness and disappointing.

Once on his wavelength, however, there is much to admire here: the tensely expressive lyricism that

Jones can distil from brooding darkness, the sheer resourceful skill of his thematic working, the passionate

eloquence that is sometimes won from this. He is, it seems to me, something of a hit-and-miss composer:

both the Ninth Symphony and the cantata begin well (a striking group of pithy ideas, absorbingly

discussed; a warmly melodious, amply singable hymn) but end disappointingly (the symphony with

what sounds like a sonata movement that never gets beyond the exposition, the cantata with a heavy-

limbed fugue, a glumly inadequate response to Vaughan's ecstatic jubilance). But the dark, urgent

drama of the Sixth Symphony, the lift-off that Jones's brusquely springy rhythms can attain, above

all a sort of hard-won sustained intensity of utterance (the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony is

a good example) make him a genuine symphonist, one whose wrestlings with the form are absorbing

even when they don't quite come off. The performances are excellent throughout; the recordings are

beginning to sound their age (a patch or two of glare) but are perfectly serviceable."

Gramophone

The sharing period for these albums has ended. No more requests, and no re-ups of my material please!