Vinphonic

06-14-2018, 10:27 PM

The Legacy of Japanese Composers

Tomoyuki Asakawa

A nextday/Herr Salat/Vinphonic/Zipper Co-Production

Main Title (http://picosong.com/wcTeM/) / Fight! (http://picosong.com/wcTCR/) / Towards Zion (http://picosong.com/wcTCf/)

Introduction by The Zipper:

There's a chance if you watch Anime or play Japanese video games, you’ve heard the sound of Tomoyuki Asakawa before listening to any of his own works. Any time there is a harp in the background, there is a 90% chance the musician playing it is Asakawa.

As of this moment, Asakawa is Japan’s foremost harpist, performing everywhere from anime to films to live concerts. He seems to be in demand as a harpist, and quite content with his current career. But there is far more to this supposedly mere harpist than his current performance would suggest.

Occasionally, musicians who are session players or playing in an orchestra also have an interest in composing, such as violinist Hajime Mizoguchi and Jazz pianist Bill Evans. Asakawa is one such double act, but unlike many others, his descent into playing harp full-time is something of a mystery and a huge shame. Believe it or not, decades ago in the 80s and 90s, Tomoyuki Asakawa was one of the most promising Japanese orchestral composers in media. A musical prodigy who started playing piano at 4 and won the national Japanese Yamaha Electone junior competition at age 10, among many other prestigious awards, he would later be recruited by Yamaha to be one of their musical envoys, playing piano across the globe under their sponsorship in various large concerts. At the very early age of 15, he attended the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Over the next 6 years in the university, he received the equivalent of a masters in composition (and believe it or not, the organ) as part of his studies (to my knowledge, he never learned to play harp in college or any professional training environment).

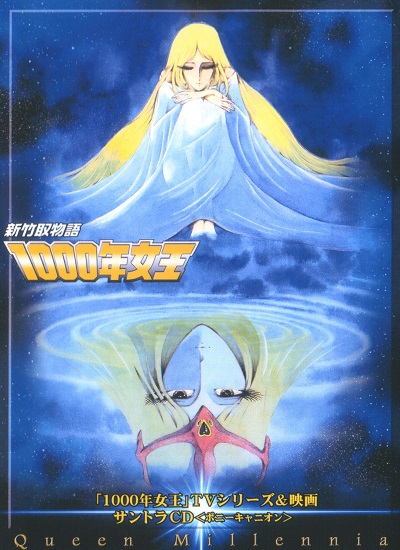

Even in college, Asakawa’s reputation as an orchestral wiz kid seemed to be widely known. As a result, he caught his big break in 1981 at the tender age of 20 when producer/guitarist/singer/songwriter/composer/actor Ryudo Uzaki recruited him to work as the composer for the anime movie Queen Millennia and the live-action movie Station (Eki). Although he was officially credited as only an orchestrator, Asakawa’s contributions far surpassed that of his credits, where he essentially took Uzaki’s melodies and wrote an entire orchestral soundtrack around them. This marked the beginning of his career, and over the next 20 years, he would create some of the best orchestral works ever written in Japan. This compilation will cover most of his work over the course of his career, from the 80s to the 2000s, in anime, live-action, and even documentaries.

If one were to describe Asakawa’s music in a single phrase, it would be “Golden Age”. His music evokes the powerful melodramatic and classical feel of 1940s and 50s Hollywood, most notable for composers such as Max Steiner and Erich Korngold. Intense and longing melodies, grand brass fanfares, all sections of the orchestra moving at once- such music was what defined the Hollywood sound. While it would be considered corny or Disney-like by modern standards, there is no question that the technical ability required to write this music far surpasses anything being needed to be a film composer for Hollywood nowadays.

Sadly, it will most likely remain a mystery why someone as talented as Asakawa surrendered his baton to make a living playing the harp, despite being deeply respected by the entire classical community of Japan and even encouraged by Michiru Oshima and Yasunori Mitsuda to return as a full-time composer, but each time this is brought up on his social media, he politely avoids the topic. He himself is also a director for the prestigious Japanese Composers and Arrangers Association. He knows just about and has worked with almost every composer in Japan. Maybe choosing to play the harp was voluntary on his part, for personal or private reasons. After all, this is the same man who refused to score the old Devilman OVA because he was a Christian.

Or he may have had to quit out of mere lack of demand for his music after Goddess. While other orchestral composers elsewhere already had it tough because anything that didn’t sound like Zimmer was frowned upon, it’s perhaps even more difficult for Asakawa, who lives and dies evoking an era of Hollywood that died a long, long time ago. Even the aforementioned Korngold, who was active at the peak of the golden age of Hollywood in the 30s to 50s, lived to see his music lose favor in the eyes of the public.

Despite both being born as musical prodigies, neither men had the power to have enough opportunity to work with an orchestra whenever they pleased. Asakawa’s latest scores were for two Japanese films in 2010 and 2012, both small in scale and neither one receiving any soundtrack release. Since then, he hasn’t composed anything new.

However, at only 58 years old, he is far from retirement age, and even if he doesn’t write for large orchestras anymore, he still actively composes for himself and his harp, and helps others arrange music for concerts and media works, often times uncredited. And in the environment of Japan, where musical trends never truly die, maybe Asakawa will be lucky enough to find another great gig as a composer some day again. Five Star Stories gets quite the publicity lately, with the Manga going strong and being on the cover of various magazines so perhaps there might be a chance of him returning if they announce a remake/sequel for FFS. Until then, please enjoy this large collection of his music, and remind yourself each time you hear a harp in the background of your favorite Japanese score that there is a possibility a certain semi-retired orchestral master played it. :)

DOWNLOAD (https://mega.nz/#!bmJHTBrS!9brZoLWOmo9egdaXXIVUoZ0hKrrDvw7yxnpRAM1l9WQ)

Bonus

Ladies and Gentlemen, Asakawa's very first pieces from 1981 (yes, before Station, making this his debut?) and his very last glorious piece with an orchestra in Golden Age style, from 2006.

Tomoyuki Asakawa/ Queen Millennia: Film Suite

Oldest Asakawa (http://picosong.com/wcpFX/)

Tomoyuki Asakawa/ Goodbye Summer's Day

The latest/final orchestral Asakawa? (http://picosong.com/wcp3x/)

These two belong in the "symphonic arrangement" folder.

He also did a new artist arrangement album in 2017 called LUNA, but its just strings.

Below is a detailed description and evaluation of his scores by Zipper which is very much in alignment with my own opinion:

The Five Star Stories is arguably Asakawa’s most well-known work, and my personal favorite of his. Rather than taking the grandiose way of sci-fi like Williams’ Star Wars, Asakawa takes a more tender and almost ballet-like approach like something you would hear from Tchaikovsky. “Elegant Escape” is the prime example of this, and its dashing brass and winds give it a light yet tense beauty. Of course, the golden age romanticism is still occasionally there, in tracks such as “Beyond the Universe”, which is literally a Korngold piece. Asakawa also incorporates his organ composition knowledge and uses it to give the soundtrack a slight touch of sci-fi, decades before Zimmer’s less glamorous attempt in Interstellar. But what puts this soundtrack at the very top for me is just how cohesive it is. Like any great soundtrack, the music is powerful enough to tell the story even without the visuals of the film (even though it is missing roughly 20 minutes of music from the film). There is some fantastic thematic development in this soundtrack, from the various permutations of the Fatima (love) theme to Sopp’s theme. This is a soundtrack that came straight out of 1940s golden age Hollywood. Fitting for a film that centers around a giant golden robot rescuing a damsel in distress. Ironically enough, he would work on another film for the same franchise two decades later (Gothicmade)- as a harpist.

Wataru is a difficult soundtrack to talk about, because the circumstances surrounding it are a bit strange. Co-composed by both Asakawa and Toshihiko Sahashi, there is a very notable contrast between their music, played by what sounds like a jazz-hybrid orchestra. Thankfully, despite the faulty soundtrack credits (especially the third one), it is easy to tell who composed what. While Sahashi took charge of the more 90s synth and jazz/funk tracks that were typical of both his earlier works and other super robot soundtracks of its time, Asakawa wrote a sea-farring swashbuckling orchestral monster. This compilation contains only the Asakawa tracks, arranged in a less schizophrenic manner than what was originally presented on the discs.

On a paper, this may be a top contender for not only Asakawa’s most technically accomplished soundtrack, but also one of the best scores ever written in the history of media music, full-stop. Forget Cutthroat Island, this was THE swashbuckler of the 90s. Before, I used the term “orchestral monster” to describe the music, and that is exactly what this is. The entire soundtrack has the orchestra moving in all directions everywhere, and requires multiple listening to appreciate just how much is layered in each individual piece. Strings, brass, and woodwinds play and shift in tandem, and the poor 40-piece jazz hybrid orchestra is trying their very best to keep up with Asakawa’s instrumental chaos. And boy, there is a lot of chaos in this soundtrack. While never atonal, the brunt of Wataru has a rather overbearingly loud, dissonant quality to it similar to Alex North’s Spartacus. This stuff is not easy to listen to. The highlight of the score, “Fight Dragon Round” is something that sounds like a hellish doomed battle between a tiny ship and a giant sea creature, while the Demon pieces such as “Ruler of the Fortress” would make you think Asakawa was scoring the Apocalypse. But like Spartacus, there is a lot of melodic optimism underneath that wall of dissonance that keeps the music all together. At its heart, Wataru is still a golden age swashbuckler. “To Tomorrow” is very much a typical Korngold intro, while “Into the Vortex” is the sort of thing you would expect to hear in the background when Errol Flynn swoops in to save the day. The first half of “Lion Dragon” and its reprise, “Phoenix Dragon Birth” are spectacular showcases of grandiose heroism and triumph, while “Sheng Temple” and “Heart of Fantasia” are both gorgeous romantic pieces. There is also a small dose of impressionist beauty with pieces like “Glow Fantasia” and “Moon Goddess”.

If there is one negative to say about this soundtrack, it’s the aforementioned studio jazz-hybrid ensemble is completely out of its league when dealing with Asakawa. Not only are there portions that have lacking delivery, the ensemble itself also emits a timbre that is at odds with the music, turning powerful dissonant trumpet runs into strange swing flings. It’s clear that this orchestra was assembled more to suit the jazzy style of Sahashi for this soundtrack. Still, for a 40-piece orchestra trying to play music made for a 120-piece orchestra, they pulled off a valiant effort.

The Candidate for Goddess is Asakawa’s final anime work, and is quite literally a space opera of a score. While some portions of it do contain carry-overs from the dissonant action of Wataru such as “Attack of Victims” (also occasionally suffering from the “jazz timbre” of Wataru, leading me to suspect the two soundtracks were recorded around the same time), the soundtrack as a whole has a jubilant early Broadway sound to it, made clear from its opening piece “Towards Zion” and others such as “Launch of Goddesses”. Some pieces like “Fellow Students of G.O.A.” almost sound like they could have came from a 1950s family romcom. Asakawa also dips into new territory by providing a wordless opera piece with “Blue and Infinite.” Of course, there is more impressionist music fitting of for the depths of space, such as in “Good-bye, My Home Town” or “Ingrid of My Adoration”, which could have came right out of Star Trek. However, the real star of the soundtrack is the gorgeous and appropriately named “Brilliance”, a majestic vocal piece with many melodic variations throughout the soundtrack. While Candidate is not my favorite Asakawa work, I still consider it a great one to end his anime career with.

Jungle Emperor Leo is somewhat of a continuation of the grand jungle adventure sound of Keniya Boy, but with a lighter pastoral atmosphere and occasional mickey-mousing to match the tastes of Osamu Tezuka. There are two versions of the music: Symphonic Fantasy and Symphonic Suite. Make no mistake, these two are different. While Symphonic Fantasy was written to be used in the show, Symphonic Suite takes the themes and turns them into a concert work. While the nature of the music is unfortunately rather fragmented even in the suite, everything still sounds beautiful. The grand highlight comes from the Miklos Rozsa-like movement of the third part of the symphonic suite, which contrasts the exotic natural wildlife with invincible military might.

Keniya Boy may not have been the first anime soundtrack Asakawa worked on, but it is the first one where he was given the entire spotlight. And boy, did he use that spotlight. Although it was credited to Ryudo Uzaki, with Asakawa once again being relegated to a mere orchestrator credit, there is no question that the music is entirely his. Unfortunately this soundtrack only contains around half an hour of score despite the film itself having roughly an hour and a half of original music, with no future soundtracks since to give a full listening experience. Still, what is here is good enough to immerse oneself in the world of the film. A mixture of 40s jungle adventure and 70s sci-fi, Asakawa writes music to match. From the Prologue, the viewer is punched in the face with a powerful introduction in the vein of Holst’s Jupiter, before moving into a glorious romantic melody and then a wonderfully luscious waltz. The sci-fi influences reveal themselves in “Grand Kilimanjaro”, where the whirling woodwinds give the impression of the beautiful unknown, before turning into another grand romantic and contemplative melody with a grand crescendo comparable to the climax of Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo. Tender themes such as “Savanna Sunset” and “Zega and Wataru” contrast with the vicious power of “WILD BOY KENIYA”, and everything wraps up nicely with the Epilogue, which reprises the various themes and gives as cinematic a goodbye as any grand old adventure film. This is also one of the few times where Asakawa is given a concert hall to record the music in.

Moving onto his live-action works, Rex- a Dinosaur Story was a horrific and infamous movie often mocked by the Japanese, their equivalent of Howard the Duck. Thankfully, it didn’t stop Asakawa’s music from shining. The soundtrack plays out like a gorgeous lullaby, culminating in the beautiful “The Earth Loves You”. And while Candidate for Goddess had a Broadway-like sound to some of it pieces, Asakawa delivers a straight-up 1950s Broadway piece with the Main Title, including an English choir that don’t do too bad of a job sounding like the real deal.

The Asian Highway was a score written for an NHK documentary, and is quite different from the rest of Asakawa’s work. While the intro piece is typical of Asakawa, the rest of the soundtrack takes influences from Japanese melodies and Vaugh Williams’ pastoral style. The end result is a harmonically dense and breathtakingly beautiful piece of work that will soothe anyone’s soul. Despite being rather short, this soundtrack gives an impression of what a Taiga Drama score written by Asakawa would sound like.

Kizuna is also quite a departure from the usual Asakawa golden age sound. Not only is the score more muted in its romanticism, Asakawa also writes some straight-up atonal music for it. The rest of the soundtrack consists of impressionist chamber pieces. While he doesn’t flex his orchestral muscles here as much as he does in his other soundtracks (likely due to the smaller ensemble), there is still much to like. The highlight of this score is the marvelous “Daybreak”, a passionate yet beautiful piece that sounds like a combination of Jerry Goldsmith’s Chinatown and Miklos Rozsa’s Spellbound.

From a Sheet of Scenery is a small collection of chamber music that is more classical in nature. While it’s nothing dramatic or complex, it’s a very pleasant listening experience, with some virtuoso solos. Great music for a sunny afternoon.

Daisy Day is a surprisingly popular score, and rather than being a cohesive soundtrack, it’s a collection of tunes, mostly written and played by Asakawa on his harp. Rather than the music itself, this soundtrack is indicative of where Asakawa is nowadays in his life and career.

Also included is a folder of various orchestral rearrangements of pop songs and film suites. Even when working with the melodies of others, Asakawa never once loses his own voice.

Candidate for Goddess is from my CD-Rip. Five Star Stories, Wataru, Jungle Emperor, Asian Highway and Kizuna were provided by Herr Salat and nextday. A sheet of Scenery is by nextday as is most of the orchestral arrangements. Kenya Boy was provided by Zipper, Daisy Day by sugimania.

Tomoyuki Asakawa

A nextday/Herr Salat/Vinphonic/Zipper Co-Production

Main Title (http://picosong.com/wcTeM/) / Fight! (http://picosong.com/wcTCR/) / Towards Zion (http://picosong.com/wcTCf/)

Introduction by The Zipper:

There's a chance if you watch Anime or play Japanese video games, you’ve heard the sound of Tomoyuki Asakawa before listening to any of his own works. Any time there is a harp in the background, there is a 90% chance the musician playing it is Asakawa.

As of this moment, Asakawa is Japan’s foremost harpist, performing everywhere from anime to films to live concerts. He seems to be in demand as a harpist, and quite content with his current career. But there is far more to this supposedly mere harpist than his current performance would suggest.

Occasionally, musicians who are session players or playing in an orchestra also have an interest in composing, such as violinist Hajime Mizoguchi and Jazz pianist Bill Evans. Asakawa is one such double act, but unlike many others, his descent into playing harp full-time is something of a mystery and a huge shame. Believe it or not, decades ago in the 80s and 90s, Tomoyuki Asakawa was one of the most promising Japanese orchestral composers in media. A musical prodigy who started playing piano at 4 and won the national Japanese Yamaha Electone junior competition at age 10, among many other prestigious awards, he would later be recruited by Yamaha to be one of their musical envoys, playing piano across the globe under their sponsorship in various large concerts. At the very early age of 15, he attended the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Over the next 6 years in the university, he received the equivalent of a masters in composition (and believe it or not, the organ) as part of his studies (to my knowledge, he never learned to play harp in college or any professional training environment).

Even in college, Asakawa’s reputation as an orchestral wiz kid seemed to be widely known. As a result, he caught his big break in 1981 at the tender age of 20 when producer/guitarist/singer/songwriter/composer/actor Ryudo Uzaki recruited him to work as the composer for the anime movie Queen Millennia and the live-action movie Station (Eki). Although he was officially credited as only an orchestrator, Asakawa’s contributions far surpassed that of his credits, where he essentially took Uzaki’s melodies and wrote an entire orchestral soundtrack around them. This marked the beginning of his career, and over the next 20 years, he would create some of the best orchestral works ever written in Japan. This compilation will cover most of his work over the course of his career, from the 80s to the 2000s, in anime, live-action, and even documentaries.

If one were to describe Asakawa’s music in a single phrase, it would be “Golden Age”. His music evokes the powerful melodramatic and classical feel of 1940s and 50s Hollywood, most notable for composers such as Max Steiner and Erich Korngold. Intense and longing melodies, grand brass fanfares, all sections of the orchestra moving at once- such music was what defined the Hollywood sound. While it would be considered corny or Disney-like by modern standards, there is no question that the technical ability required to write this music far surpasses anything being needed to be a film composer for Hollywood nowadays.

Sadly, it will most likely remain a mystery why someone as talented as Asakawa surrendered his baton to make a living playing the harp, despite being deeply respected by the entire classical community of Japan and even encouraged by Michiru Oshima and Yasunori Mitsuda to return as a full-time composer, but each time this is brought up on his social media, he politely avoids the topic. He himself is also a director for the prestigious Japanese Composers and Arrangers Association. He knows just about and has worked with almost every composer in Japan. Maybe choosing to play the harp was voluntary on his part, for personal or private reasons. After all, this is the same man who refused to score the old Devilman OVA because he was a Christian.

Or he may have had to quit out of mere lack of demand for his music after Goddess. While other orchestral composers elsewhere already had it tough because anything that didn’t sound like Zimmer was frowned upon, it’s perhaps even more difficult for Asakawa, who lives and dies evoking an era of Hollywood that died a long, long time ago. Even the aforementioned Korngold, who was active at the peak of the golden age of Hollywood in the 30s to 50s, lived to see his music lose favor in the eyes of the public.

Despite both being born as musical prodigies, neither men had the power to have enough opportunity to work with an orchestra whenever they pleased. Asakawa’s latest scores were for two Japanese films in 2010 and 2012, both small in scale and neither one receiving any soundtrack release. Since then, he hasn’t composed anything new.

However, at only 58 years old, he is far from retirement age, and even if he doesn’t write for large orchestras anymore, he still actively composes for himself and his harp, and helps others arrange music for concerts and media works, often times uncredited. And in the environment of Japan, where musical trends never truly die, maybe Asakawa will be lucky enough to find another great gig as a composer some day again. Five Star Stories gets quite the publicity lately, with the Manga going strong and being on the cover of various magazines so perhaps there might be a chance of him returning if they announce a remake/sequel for FFS. Until then, please enjoy this large collection of his music, and remind yourself each time you hear a harp in the background of your favorite Japanese score that there is a possibility a certain semi-retired orchestral master played it. :)

DOWNLOAD (https://mega.nz/#!bmJHTBrS!9brZoLWOmo9egdaXXIVUoZ0hKrrDvw7yxnpRAM1l9WQ)

Bonus

Ladies and Gentlemen, Asakawa's very first pieces from 1981 (yes, before Station, making this his debut?) and his very last glorious piece with an orchestra in Golden Age style, from 2006.

Tomoyuki Asakawa/ Queen Millennia: Film Suite

Oldest Asakawa (http://picosong.com/wcpFX/)

Tomoyuki Asakawa/ Goodbye Summer's Day

The latest/final orchestral Asakawa? (http://picosong.com/wcp3x/)

These two belong in the "symphonic arrangement" folder.

He also did a new artist arrangement album in 2017 called LUNA, but its just strings.

Below is a detailed description and evaluation of his scores by Zipper which is very much in alignment with my own opinion:

The Five Star Stories is arguably Asakawa’s most well-known work, and my personal favorite of his. Rather than taking the grandiose way of sci-fi like Williams’ Star Wars, Asakawa takes a more tender and almost ballet-like approach like something you would hear from Tchaikovsky. “Elegant Escape” is the prime example of this, and its dashing brass and winds give it a light yet tense beauty. Of course, the golden age romanticism is still occasionally there, in tracks such as “Beyond the Universe”, which is literally a Korngold piece. Asakawa also incorporates his organ composition knowledge and uses it to give the soundtrack a slight touch of sci-fi, decades before Zimmer’s less glamorous attempt in Interstellar. But what puts this soundtrack at the very top for me is just how cohesive it is. Like any great soundtrack, the music is powerful enough to tell the story even without the visuals of the film (even though it is missing roughly 20 minutes of music from the film). There is some fantastic thematic development in this soundtrack, from the various permutations of the Fatima (love) theme to Sopp’s theme. This is a soundtrack that came straight out of 1940s golden age Hollywood. Fitting for a film that centers around a giant golden robot rescuing a damsel in distress. Ironically enough, he would work on another film for the same franchise two decades later (Gothicmade)- as a harpist.

Wataru is a difficult soundtrack to talk about, because the circumstances surrounding it are a bit strange. Co-composed by both Asakawa and Toshihiko Sahashi, there is a very notable contrast between their music, played by what sounds like a jazz-hybrid orchestra. Thankfully, despite the faulty soundtrack credits (especially the third one), it is easy to tell who composed what. While Sahashi took charge of the more 90s synth and jazz/funk tracks that were typical of both his earlier works and other super robot soundtracks of its time, Asakawa wrote a sea-farring swashbuckling orchestral monster. This compilation contains only the Asakawa tracks, arranged in a less schizophrenic manner than what was originally presented on the discs.

On a paper, this may be a top contender for not only Asakawa’s most technically accomplished soundtrack, but also one of the best scores ever written in the history of media music, full-stop. Forget Cutthroat Island, this was THE swashbuckler of the 90s. Before, I used the term “orchestral monster” to describe the music, and that is exactly what this is. The entire soundtrack has the orchestra moving in all directions everywhere, and requires multiple listening to appreciate just how much is layered in each individual piece. Strings, brass, and woodwinds play and shift in tandem, and the poor 40-piece jazz hybrid orchestra is trying their very best to keep up with Asakawa’s instrumental chaos. And boy, there is a lot of chaos in this soundtrack. While never atonal, the brunt of Wataru has a rather overbearingly loud, dissonant quality to it similar to Alex North’s Spartacus. This stuff is not easy to listen to. The highlight of the score, “Fight Dragon Round” is something that sounds like a hellish doomed battle between a tiny ship and a giant sea creature, while the Demon pieces such as “Ruler of the Fortress” would make you think Asakawa was scoring the Apocalypse. But like Spartacus, there is a lot of melodic optimism underneath that wall of dissonance that keeps the music all together. At its heart, Wataru is still a golden age swashbuckler. “To Tomorrow” is very much a typical Korngold intro, while “Into the Vortex” is the sort of thing you would expect to hear in the background when Errol Flynn swoops in to save the day. The first half of “Lion Dragon” and its reprise, “Phoenix Dragon Birth” are spectacular showcases of grandiose heroism and triumph, while “Sheng Temple” and “Heart of Fantasia” are both gorgeous romantic pieces. There is also a small dose of impressionist beauty with pieces like “Glow Fantasia” and “Moon Goddess”.

If there is one negative to say about this soundtrack, it’s the aforementioned studio jazz-hybrid ensemble is completely out of its league when dealing with Asakawa. Not only are there portions that have lacking delivery, the ensemble itself also emits a timbre that is at odds with the music, turning powerful dissonant trumpet runs into strange swing flings. It’s clear that this orchestra was assembled more to suit the jazzy style of Sahashi for this soundtrack. Still, for a 40-piece orchestra trying to play music made for a 120-piece orchestra, they pulled off a valiant effort.

The Candidate for Goddess is Asakawa’s final anime work, and is quite literally a space opera of a score. While some portions of it do contain carry-overs from the dissonant action of Wataru such as “Attack of Victims” (also occasionally suffering from the “jazz timbre” of Wataru, leading me to suspect the two soundtracks were recorded around the same time), the soundtrack as a whole has a jubilant early Broadway sound to it, made clear from its opening piece “Towards Zion” and others such as “Launch of Goddesses”. Some pieces like “Fellow Students of G.O.A.” almost sound like they could have came from a 1950s family romcom. Asakawa also dips into new territory by providing a wordless opera piece with “Blue and Infinite.” Of course, there is more impressionist music fitting of for the depths of space, such as in “Good-bye, My Home Town” or “Ingrid of My Adoration”, which could have came right out of Star Trek. However, the real star of the soundtrack is the gorgeous and appropriately named “Brilliance”, a majestic vocal piece with many melodic variations throughout the soundtrack. While Candidate is not my favorite Asakawa work, I still consider it a great one to end his anime career with.

Jungle Emperor Leo is somewhat of a continuation of the grand jungle adventure sound of Keniya Boy, but with a lighter pastoral atmosphere and occasional mickey-mousing to match the tastes of Osamu Tezuka. There are two versions of the music: Symphonic Fantasy and Symphonic Suite. Make no mistake, these two are different. While Symphonic Fantasy was written to be used in the show, Symphonic Suite takes the themes and turns them into a concert work. While the nature of the music is unfortunately rather fragmented even in the suite, everything still sounds beautiful. The grand highlight comes from the Miklos Rozsa-like movement of the third part of the symphonic suite, which contrasts the exotic natural wildlife with invincible military might.

Keniya Boy may not have been the first anime soundtrack Asakawa worked on, but it is the first one where he was given the entire spotlight. And boy, did he use that spotlight. Although it was credited to Ryudo Uzaki, with Asakawa once again being relegated to a mere orchestrator credit, there is no question that the music is entirely his. Unfortunately this soundtrack only contains around half an hour of score despite the film itself having roughly an hour and a half of original music, with no future soundtracks since to give a full listening experience. Still, what is here is good enough to immerse oneself in the world of the film. A mixture of 40s jungle adventure and 70s sci-fi, Asakawa writes music to match. From the Prologue, the viewer is punched in the face with a powerful introduction in the vein of Holst’s Jupiter, before moving into a glorious romantic melody and then a wonderfully luscious waltz. The sci-fi influences reveal themselves in “Grand Kilimanjaro”, where the whirling woodwinds give the impression of the beautiful unknown, before turning into another grand romantic and contemplative melody with a grand crescendo comparable to the climax of Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo. Tender themes such as “Savanna Sunset” and “Zega and Wataru” contrast with the vicious power of “WILD BOY KENIYA”, and everything wraps up nicely with the Epilogue, which reprises the various themes and gives as cinematic a goodbye as any grand old adventure film. This is also one of the few times where Asakawa is given a concert hall to record the music in.

Moving onto his live-action works, Rex- a Dinosaur Story was a horrific and infamous movie often mocked by the Japanese, their equivalent of Howard the Duck. Thankfully, it didn’t stop Asakawa’s music from shining. The soundtrack plays out like a gorgeous lullaby, culminating in the beautiful “The Earth Loves You”. And while Candidate for Goddess had a Broadway-like sound to some of it pieces, Asakawa delivers a straight-up 1950s Broadway piece with the Main Title, including an English choir that don’t do too bad of a job sounding like the real deal.

The Asian Highway was a score written for an NHK documentary, and is quite different from the rest of Asakawa’s work. While the intro piece is typical of Asakawa, the rest of the soundtrack takes influences from Japanese melodies and Vaugh Williams’ pastoral style. The end result is a harmonically dense and breathtakingly beautiful piece of work that will soothe anyone’s soul. Despite being rather short, this soundtrack gives an impression of what a Taiga Drama score written by Asakawa would sound like.

Kizuna is also quite a departure from the usual Asakawa golden age sound. Not only is the score more muted in its romanticism, Asakawa also writes some straight-up atonal music for it. The rest of the soundtrack consists of impressionist chamber pieces. While he doesn’t flex his orchestral muscles here as much as he does in his other soundtracks (likely due to the smaller ensemble), there is still much to like. The highlight of this score is the marvelous “Daybreak”, a passionate yet beautiful piece that sounds like a combination of Jerry Goldsmith’s Chinatown and Miklos Rozsa’s Spellbound.

From a Sheet of Scenery is a small collection of chamber music that is more classical in nature. While it’s nothing dramatic or complex, it’s a very pleasant listening experience, with some virtuoso solos. Great music for a sunny afternoon.

Daisy Day is a surprisingly popular score, and rather than being a cohesive soundtrack, it’s a collection of tunes, mostly written and played by Asakawa on his harp. Rather than the music itself, this soundtrack is indicative of where Asakawa is nowadays in his life and career.

Also included is a folder of various orchestral rearrangements of pop songs and film suites. Even when working with the melodies of others, Asakawa never once loses his own voice.

Candidate for Goddess is from my CD-Rip. Five Star Stories, Wataru, Jungle Emperor, Asian Highway and Kizuna were provided by Herr Salat and nextday. A sheet of Scenery is by nextday as is most of the orchestral arrangements. Kenya Boy was provided by Zipper, Daisy Day by sugimania.