wimpel69

11-07-2014, 12:46 PM

"These are performances of the very greatest distinction,

backed by a recording of beautiful lucidity. I do urge you to hear them."

EAC-FLAC link below. This is my own rip. Complete artwork,

LOG and CUE files included. Do not share. Buy the original!

Please leave a "Like" or "Thank you" if you enjoyed this!

In 1936, the Soviet government launched an official attack against Dmitri Shostakovich's music,

calling it "vulgar, formalistic, [and] neurotic." He became an example to other Soviet composers, who

rightfully interpreted these events as a broad campaign against musical modernism. This constituted a

crisis, both in Shostakovich's career and in Soviet music as a whole; composers had no choice but to

write simple, optimistic music that spoke directly (especially through folk idioms and patriotic programs)

to the people and glorified the state.

In light of these circumstances, Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony (first performed in 1937) is a bold

composition that seems to fly in the face of his critics. Although the musical language is pared down

from that of his earlier symphonies, the Fifth eschews any hint of a patriotic program and, instead,

dwells on undeniably somber and tragic affects -- wholly unacceptable public emotions at the time.

According to the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, the government would certainly have had Shostakovich

executed for writing such a work had the public ovation at the first performance not lasted 40 minutes.

The official story, however, is quite different. An unknown commentator dubbed the symphony "the

creative reply of a Soviet artist to justified criticism," and to the work was attached an autobiographical

program focusing on the composer's metamorphosis from incomprehensible formalist to standard-

bearer of the communist party. Publicly, Shostakovich accepted the official interpretation of his work;

however, in the controversial collection of his memoirs (Testimony, by Solomon Volkov) he is quoted

as saying: "I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created

under threat...you have to be a complete oaf not to hear that."

Regardless of its philosophical underpinnings, Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5 is a masterpiece of

the orchestral repertory, poignant and economical in its conception. There is no sign of the excess of

ideas so common in the Fourth Symphony. Instead, Shostakovich deploys the orchestra sparingly and

allows the entire work to grow naturally out of just a few motives. Given some of his earlier works,

the Fifth is conservative in language. Throughout the work he allows the strings to be the dominant

orchestral force, making soloistic use of the woodwinds and horn especially effective. The Moderato

begins with a jagged, foreboding canon in the strings that forms the motivic basis for the entire

movement. The impassioned mood is occasionally interrupted by a lyrical melody with string ostinato,

later the subject of a duet for flute and horn.

The second movement (Allegretto) is a grotesque 3/4 dance which, at times, can't help but mock

itself; the brass section is featured prominently. The following Largo, a sincere and personal

outpouring of musical emotion, is said to have left the audience at the work's premiere in tears.

Significantly, it was composed during an intensely creative period following the arrest and execution

of one of Shostakovich's teachers.

The concluding Allegro non troppo has been the center of much debate: some critics consider it

a poorly constructed concession to political pressure, while others have made note of its possible

irony. While the prevailing mood is triumphant, there is some diversion to the somber and foreboding,

and it is not until the end that it takes on the overtly "big-finishy" character for which it is so noted.

Shostakovich composed his Symphony No.9 for Schumann-sized orchestra plus percussion in the

summer of 1945, and Yevgeny Mravinsky led the first performance at Leningrad on November 3 of

that year. Given the size of Shostakovich's war-haunted seventh and eighth symphonies, Joseph Stalin

expected a Ninth in 1945 that "out-Mahlered Beethoven," in the late Boris Schwarz's phrase. In

Testimony, Solomon Volkov recalled the composer's saying, "They wanted a fanfare from me, an

ode, a majestic Ninth....I doubt that Stalin ever questioned his own genius or greatness. But when

the war against Hitler was won, he went off the deep end, like a frog puffing himself up to the size

of an ox, and now I was supposed to write an apotheosis of Stalin. I simply could not....My

stubbornness cost me dearly."

Volkov called the Ninth a work "full of sarcasm and bitterness." Disguised as an homage to Haydn,

it was Shostakovich's shortest symphony since the Second of 1927, despite having five movements

(the last three are played without pause). In an effort to shield Shostakovich from political fallout,

conductor Mravinsky called the new symphony "a joyous sigh of relief...a work directed against

philistinism, which ridicules complacency and bombast, the desire to rest on one's laurels." Putting

on a good face, the Soviet hierarchy echoed Mravinsky, but only temporarily.

By and large, Western critics dismissed the work as trivial. However, in his 1990 book The New

Shostakovich, Ian MacDonald asserted that "only a dunce could have failed to realize the composer

was up to something," pointing out the code-bearing nature of recurring notes and rhythms. A

"Stalin motif" is frighteningly present -- always two notes, one usually short, one long -- from its

raucous first appearance, without musical point, in the double-exposition of a giddy Allegro

movement. The opening "mimic[s] the ordinary citizen's carefree relief at the victorious conclusion

of the war. the second subject -- a crude quick-march, led by a two-note, tonic-dominant

trombone -- is clearly symbolic of the Vozhd [Stalin]." MacDonald hears "fights breaking out

[and] for a hectic moment the music continues in two keys until the trombone wrests control,"

whereupon strings capitulate "and the reprise ends on sneering trills, the quick-march in control."

A Moderato movement follows, with a B minor main subject for clarinet that is "wan, sad-faced,

with a telltale two-note pendant," and "a heel-dragging" second one: "a chain of two-note cells

[that] subtly mock conventional grief." Horns "warn off [the] real feeling" that breaks through

briefly, whereupon "happy-face clowns [usher in] a cheery scherzo...another street party

[as in the first movement] that goes violently wrong."

Menacing brass octaves begin the fourth movement; then a bassoon recitative sends mixed

signals, "another mask" that leaves the strings uneasy. The Allegretto finale "erupts into

action....A dark whirlwind drives the movement to a climax of teetering expectation -- but

all that emerges is the clownish main theme, hammered out by the entire orchestra.

Shostakovich's contempt is scalding. Here are your leaders, the music jeers: circus clowns.

Point made, [he] summons a helter-skelter coda and slams [the Ninth] shut."

For MacDonald it is "an open gesture of dissent [that] ruthlessly targeted Stalinism....

Wagnerisms, the most prominent being an allusion to Wotan's Leitmotif in the fourth

movement, are probable expressions of the view, outlined in Testimony, of Stalin and Hitler

as 'spiritual relatives.'" Shostakovich paid dearly indeed for the snub; he was damned in

1948 as a "formalist" and blacklisted, leaving him only movie scores for income. After

Stalin's death in 1953 he finished a Tenth Symphony, in whose scherzo the Vozhd himself

makes one last, unforgettably terrifying appearance.

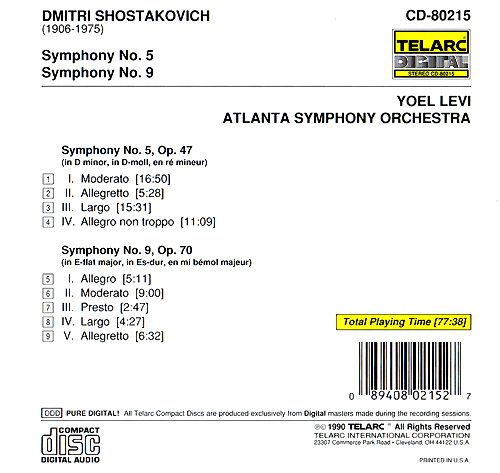

[B]Music Composed by

Dmitri Shostakovich

Played by the

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by

Yoel Levi

"Perhaps I've listened to too many Shostakovich Fifths lately; I must confess that I was not greatly

looking forward to another, and from (set beside the distinguished list of names above) unseeded

players, too. It was a great pleasure to have my prejudices destroyed within a few pages. Yoel Levi

is obviously a very fine conductor indeed, and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra play like heroes.

These readings are among the very best of either symphony on record; indeed, at the end of Levi's

Ninth (irresistibly exuberant, but with that poignantly elegiac Largo audibly casting shadows backward

to the second movement as well as onward into the finale's only gradually cast off anxiety) I was

ready to recommend this coupling above all its rivals.

Come now, said I to myself, you've managed in the past to pick ungrateful holes in Decca's overly

sumptuous recording for Haitink and their subfusc sound for Ashkenazy, in Kondrashin's (Le Chant du

Monde/Harmonia Mundi) hasty way with the first movement of the Fifth and Rozhdestvensky's

(Olympia/Target) slight aroma of greasepaint; surely you can contrive to find something disagreeable

to say about Levi, his orchestra or the Telarc engineers? Well, I suppose I could observe that Levi's

intensification of the climax of the Fifth's first movement with a martially stamped staccato will not be

to everyone's taste, but it is to mine. Or that unless my ears are deceiving me he doubles some wind

lines in the finale of the Ninth with violins, but I rather like that effect too. So I shall just have to fall

back on saying that the leader is a bit too heart-on-sleeve in the coda of the first movement of the Fifth.

I really can't think of any other drawback these performances have. Their most conspicuous surface

virtue is their dynamic range at the lower end of the spectrum. In the Largo of the Fifth Symphony

Shostakovich divides the violins into three and the violas and cellos both into two sections. Partly

to obtain rich string textures of course, but also, one realizes from Levi's reading, because he

sometimes wants the expressive resource of a small group of strings playing really quietly, and

the pianissimos achieved here are quite magical. Dynamics, indeed, are very carefully observed

throughout, and it is this above all, without the need for any ostentatious acting, that gives such

a troubled shadow to the middle section of the Ninth Symphony's second movement. Indeed,

there are no applied expressive 'effects' in these readings: they have great emotional power,

but it comes from a scrupulous gauging of what Shostakovich meant by a pp subito, an f where

one would have expected an ff, and apparently puzzlingly isolated espr. markings (there are

but two in that second movement of the Ninth Symphony, neither of them in an obvious place,

but Levi knows where they are, and why).

In fact my listening notes on this pair of performances read like a catalogue of virtues:

admirable brass playing (including a very Russian-sounding trumpet in the scherzo of the Ninth),

a recording which never gives a harsh edge even to Shostakovich's highest-lying string lines,

a most moving Largo in the Fifth, with a nobly built climax and a deathly pale dying away in

the coda, a sensitively played bassoon solo in the Largo of the Ninth, splendidly controlled

tempos throughout.... it would be fruitless to continue. These are performances of the very

greatest distinction, backed by a recording of beautiful lucidity. I do urge you to hear them.

Michael Oliver, Gramophone

DOWNLOAD LINK - https://mega.co.nz/#!L4RSUagK!TI9jY4hwKVppFVQApUVIszWZz8uLb91HWyjgrKl v3QM

Source: Telarc CD, 1990 (my rip!)

Format: FLAC(RAR), DDD Stereo, Level: -5

File Size: 327 MB (incl. artwork, booklet, log & cue)

Enjoy! Don't share! Buy the origina! Please leave a "Like" or "Thank you" if you enjoyed this! :)

backed by a recording of beautiful lucidity. I do urge you to hear them."

EAC-FLAC link below. This is my own rip. Complete artwork,

LOG and CUE files included. Do not share. Buy the original!

Please leave a "Like" or "Thank you" if you enjoyed this!

In 1936, the Soviet government launched an official attack against Dmitri Shostakovich's music,

calling it "vulgar, formalistic, [and] neurotic." He became an example to other Soviet composers, who

rightfully interpreted these events as a broad campaign against musical modernism. This constituted a

crisis, both in Shostakovich's career and in Soviet music as a whole; composers had no choice but to

write simple, optimistic music that spoke directly (especially through folk idioms and patriotic programs)

to the people and glorified the state.

In light of these circumstances, Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony (first performed in 1937) is a bold

composition that seems to fly in the face of his critics. Although the musical language is pared down

from that of his earlier symphonies, the Fifth eschews any hint of a patriotic program and, instead,

dwells on undeniably somber and tragic affects -- wholly unacceptable public emotions at the time.

According to the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, the government would certainly have had Shostakovich

executed for writing such a work had the public ovation at the first performance not lasted 40 minutes.

The official story, however, is quite different. An unknown commentator dubbed the symphony "the

creative reply of a Soviet artist to justified criticism," and to the work was attached an autobiographical

program focusing on the composer's metamorphosis from incomprehensible formalist to standard-

bearer of the communist party. Publicly, Shostakovich accepted the official interpretation of his work;

however, in the controversial collection of his memoirs (Testimony, by Solomon Volkov) he is quoted

as saying: "I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created

under threat...you have to be a complete oaf not to hear that."

Regardless of its philosophical underpinnings, Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5 is a masterpiece of

the orchestral repertory, poignant and economical in its conception. There is no sign of the excess of

ideas so common in the Fourth Symphony. Instead, Shostakovich deploys the orchestra sparingly and

allows the entire work to grow naturally out of just a few motives. Given some of his earlier works,

the Fifth is conservative in language. Throughout the work he allows the strings to be the dominant

orchestral force, making soloistic use of the woodwinds and horn especially effective. The Moderato

begins with a jagged, foreboding canon in the strings that forms the motivic basis for the entire

movement. The impassioned mood is occasionally interrupted by a lyrical melody with string ostinato,

later the subject of a duet for flute and horn.

The second movement (Allegretto) is a grotesque 3/4 dance which, at times, can't help but mock

itself; the brass section is featured prominently. The following Largo, a sincere and personal

outpouring of musical emotion, is said to have left the audience at the work's premiere in tears.

Significantly, it was composed during an intensely creative period following the arrest and execution

of one of Shostakovich's teachers.

The concluding Allegro non troppo has been the center of much debate: some critics consider it

a poorly constructed concession to political pressure, while others have made note of its possible

irony. While the prevailing mood is triumphant, there is some diversion to the somber and foreboding,

and it is not until the end that it takes on the overtly "big-finishy" character for which it is so noted.

Shostakovich composed his Symphony No.9 for Schumann-sized orchestra plus percussion in the

summer of 1945, and Yevgeny Mravinsky led the first performance at Leningrad on November 3 of

that year. Given the size of Shostakovich's war-haunted seventh and eighth symphonies, Joseph Stalin

expected a Ninth in 1945 that "out-Mahlered Beethoven," in the late Boris Schwarz's phrase. In

Testimony, Solomon Volkov recalled the composer's saying, "They wanted a fanfare from me, an

ode, a majestic Ninth....I doubt that Stalin ever questioned his own genius or greatness. But when

the war against Hitler was won, he went off the deep end, like a frog puffing himself up to the size

of an ox, and now I was supposed to write an apotheosis of Stalin. I simply could not....My

stubbornness cost me dearly."

Volkov called the Ninth a work "full of sarcasm and bitterness." Disguised as an homage to Haydn,

it was Shostakovich's shortest symphony since the Second of 1927, despite having five movements

(the last three are played without pause). In an effort to shield Shostakovich from political fallout,

conductor Mravinsky called the new symphony "a joyous sigh of relief...a work directed against

philistinism, which ridicules complacency and bombast, the desire to rest on one's laurels." Putting

on a good face, the Soviet hierarchy echoed Mravinsky, but only temporarily.

By and large, Western critics dismissed the work as trivial. However, in his 1990 book The New

Shostakovich, Ian MacDonald asserted that "only a dunce could have failed to realize the composer

was up to something," pointing out the code-bearing nature of recurring notes and rhythms. A

"Stalin motif" is frighteningly present -- always two notes, one usually short, one long -- from its

raucous first appearance, without musical point, in the double-exposition of a giddy Allegro

movement. The opening "mimic[s] the ordinary citizen's carefree relief at the victorious conclusion

of the war. the second subject -- a crude quick-march, led by a two-note, tonic-dominant

trombone -- is clearly symbolic of the Vozhd [Stalin]." MacDonald hears "fights breaking out

[and] for a hectic moment the music continues in two keys until the trombone wrests control,"

whereupon strings capitulate "and the reprise ends on sneering trills, the quick-march in control."

A Moderato movement follows, with a B minor main subject for clarinet that is "wan, sad-faced,

with a telltale two-note pendant," and "a heel-dragging" second one: "a chain of two-note cells

[that] subtly mock conventional grief." Horns "warn off [the] real feeling" that breaks through

briefly, whereupon "happy-face clowns [usher in] a cheery scherzo...another street party

[as in the first movement] that goes violently wrong."

Menacing brass octaves begin the fourth movement; then a bassoon recitative sends mixed

signals, "another mask" that leaves the strings uneasy. The Allegretto finale "erupts into

action....A dark whirlwind drives the movement to a climax of teetering expectation -- but

all that emerges is the clownish main theme, hammered out by the entire orchestra.

Shostakovich's contempt is scalding. Here are your leaders, the music jeers: circus clowns.

Point made, [he] summons a helter-skelter coda and slams [the Ninth] shut."

For MacDonald it is "an open gesture of dissent [that] ruthlessly targeted Stalinism....

Wagnerisms, the most prominent being an allusion to Wotan's Leitmotif in the fourth

movement, are probable expressions of the view, outlined in Testimony, of Stalin and Hitler

as 'spiritual relatives.'" Shostakovich paid dearly indeed for the snub; he was damned in

1948 as a "formalist" and blacklisted, leaving him only movie scores for income. After

Stalin's death in 1953 he finished a Tenth Symphony, in whose scherzo the Vozhd himself

makes one last, unforgettably terrifying appearance.

[B]Music Composed by

Dmitri Shostakovich

Played by the

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by

Yoel Levi

"Perhaps I've listened to too many Shostakovich Fifths lately; I must confess that I was not greatly

looking forward to another, and from (set beside the distinguished list of names above) unseeded

players, too. It was a great pleasure to have my prejudices destroyed within a few pages. Yoel Levi

is obviously a very fine conductor indeed, and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra play like heroes.

These readings are among the very best of either symphony on record; indeed, at the end of Levi's

Ninth (irresistibly exuberant, but with that poignantly elegiac Largo audibly casting shadows backward

to the second movement as well as onward into the finale's only gradually cast off anxiety) I was

ready to recommend this coupling above all its rivals.

Come now, said I to myself, you've managed in the past to pick ungrateful holes in Decca's overly

sumptuous recording for Haitink and their subfusc sound for Ashkenazy, in Kondrashin's (Le Chant du

Monde/Harmonia Mundi) hasty way with the first movement of the Fifth and Rozhdestvensky's

(Olympia/Target) slight aroma of greasepaint; surely you can contrive to find something disagreeable

to say about Levi, his orchestra or the Telarc engineers? Well, I suppose I could observe that Levi's

intensification of the climax of the Fifth's first movement with a martially stamped staccato will not be

to everyone's taste, but it is to mine. Or that unless my ears are deceiving me he doubles some wind

lines in the finale of the Ninth with violins, but I rather like that effect too. So I shall just have to fall

back on saying that the leader is a bit too heart-on-sleeve in the coda of the first movement of the Fifth.

I really can't think of any other drawback these performances have. Their most conspicuous surface

virtue is their dynamic range at the lower end of the spectrum. In the Largo of the Fifth Symphony

Shostakovich divides the violins into three and the violas and cellos both into two sections. Partly

to obtain rich string textures of course, but also, one realizes from Levi's reading, because he

sometimes wants the expressive resource of a small group of strings playing really quietly, and

the pianissimos achieved here are quite magical. Dynamics, indeed, are very carefully observed

throughout, and it is this above all, without the need for any ostentatious acting, that gives such

a troubled shadow to the middle section of the Ninth Symphony's second movement. Indeed,

there are no applied expressive 'effects' in these readings: they have great emotional power,

but it comes from a scrupulous gauging of what Shostakovich meant by a pp subito, an f where

one would have expected an ff, and apparently puzzlingly isolated espr. markings (there are

but two in that second movement of the Ninth Symphony, neither of them in an obvious place,

but Levi knows where they are, and why).

In fact my listening notes on this pair of performances read like a catalogue of virtues:

admirable brass playing (including a very Russian-sounding trumpet in the scherzo of the Ninth),

a recording which never gives a harsh edge even to Shostakovich's highest-lying string lines,

a most moving Largo in the Fifth, with a nobly built climax and a deathly pale dying away in

the coda, a sensitively played bassoon solo in the Largo of the Ninth, splendidly controlled

tempos throughout.... it would be fruitless to continue. These are performances of the very

greatest distinction, backed by a recording of beautiful lucidity. I do urge you to hear them.

Michael Oliver, Gramophone

DOWNLOAD LINK - https://mega.co.nz/#!L4RSUagK!TI9jY4hwKVppFVQApUVIszWZz8uLb91HWyjgrKl v3QM

Source: Telarc CD, 1990 (my rip!)

Format: FLAC(RAR), DDD Stereo, Level: -5

File Size: 327 MB (incl. artwork, booklet, log & cue)

Enjoy! Don't share! Buy the origina! Please leave a "Like" or "Thank you" if you enjoyed this! :)